Sarah Burt and I have been scanning the many different copies of the novel in order to upload the paratext (everything not included in the text of the story itself) onto the website. We have scanned many books on the book scanning machine, nicknamed Bertha, and have many more to go. We also learned to take field notes of these books, which involves detailed observation. Ben Ostermeier has taught us, and continues to teach us, the basics of all the programs needed to upload our pictures onto the server and the website. Katie Knowles and Kayla Smith are renaming the items (paratext) we have uploaded, in order for users to locate them easier on the website. All the members meet with Dr. DeSpain each week to go over our weekly and overall goals.

Oddities in Print

While scanning the different copies of The Wide, Wide World, I found some quirky details inside the 1896 Walter Scott edition. I found a bookmark, without a date, advertising an old “life assurance” company. The front of the bookmark lists the benefits of “The Methodist and General Assurance Society Ltd.” The back of this elaborate bookmark pictures a house in the country surrounded by flowers. Another oddity in this novel is the uncut pages at the end containing the advertisements. When this book was published, not all books came ready to read, as some publishers printed a few book pages on one large sheet of folded paper, and did not cut these separate pages apart. Readers would use a tool to cut pages, much like people cut open envelopes today. Though the majority of this particular edition has its pages free to read, the last eight pages of advertisements are not precut. The reader of this particular book did not care to read the advertisements apparently. Dr. DeSpain will use a letter opener in order to tear them apart. As it stands, the four middle pages are not legible because they are hidden between other pages of advertisements. I had never seen pages left uncut, as publishers now do not print the same way as this particular book was printed. It makes book history more unique and fascinating when a book demonstrates a past technology that I had never seen/heard of before working on this project. This project has taught me so much about the various parts of books and how books were once made.

The Wide, Wide World Summer Plan

Wednesday June 1st we met for our first summer meeting. The group decided upon regular Wednesday meetings, and Elizabeth and I will additionally meet on the weekends to work on editing the text from the Sampson Low 1852 edition with ABBYY FineReader.

One of our main goals for this summer is to scan all of the paratexts from all the DES collection books and upload those to the Omeka website with descriptions. We also want to create a system of quality controlling the images and descriptions.

Dr. Anderson will work on creating a gallery of 19th century reviews for The Wide, Wide World. She will select some reviews for Elizabeth and I to transcribe and add to Omeka.

Ben will be working on the Omeka website, which entails finalizing the current web style, getting secondary pages and galleries to work, troubleshooting problems, and making the TEI plug-in work with the new version of the website.

Our newest members, Merissa and Melissa, will be getting started on doing field notes, scanning, cropping, and also working on Omeka descriptions.

The Wide, Wide World crew will definitely have their work cut out for them this summer.

–Gabby

Upcoming Omeka Update

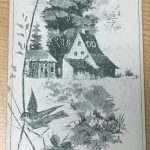

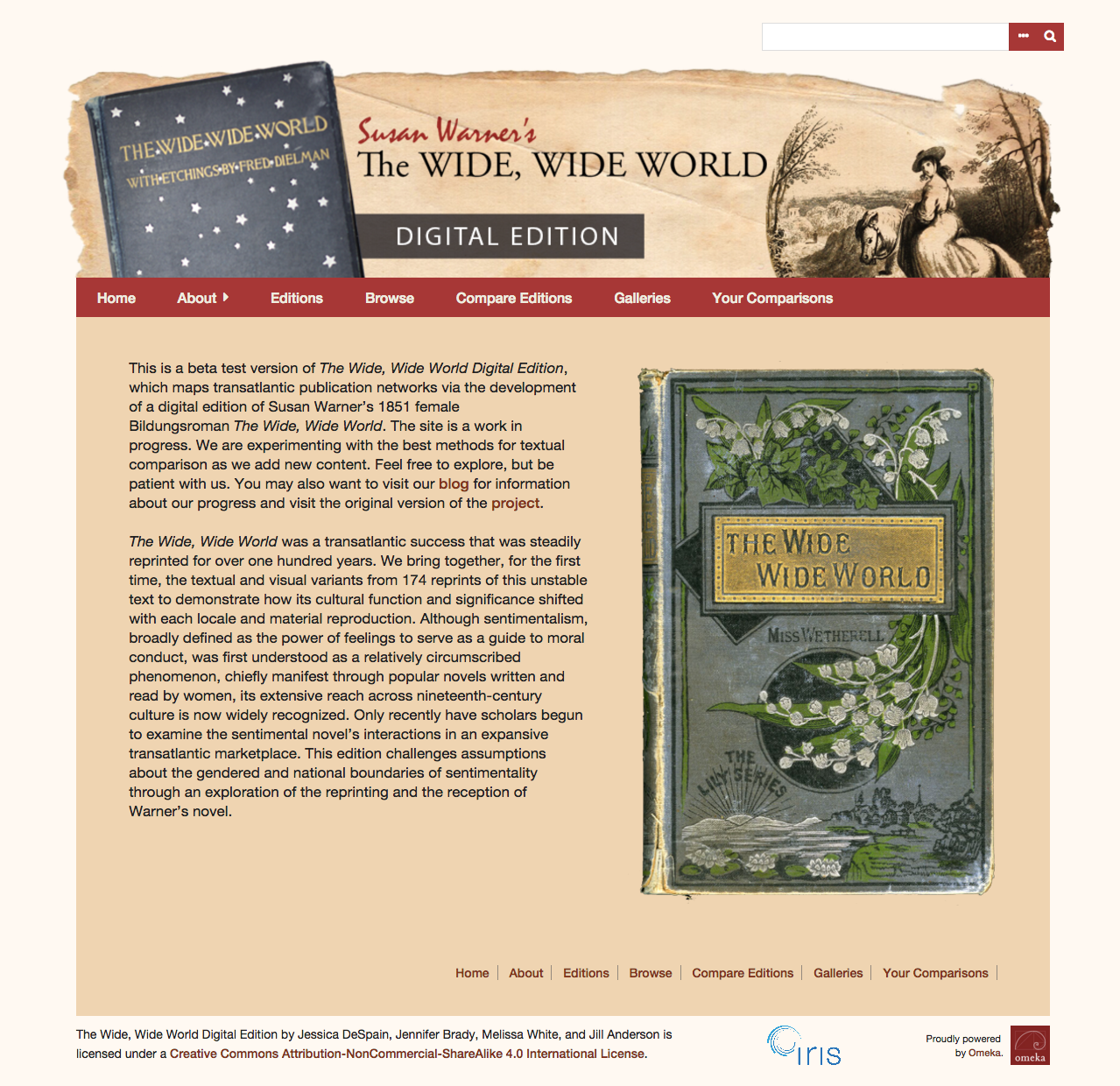

For a number of years now, the Wide, Wide World Digital Edition has used the Omeka web publishing platform. We have not, however, kept up with updates to Omeka software, as more recent versions configure their themes and database differently. The newer version has grown increasingly tempting, as it both allows for more flexibility in creating exhibits and has a built in responsive design, meaning the website will be viewable on smaller-resolution phones and tables.

Thankfully, my growing expertise in web development has given me the confidence to attempt the update. Already I made a few minor tweaks to the website’s theme this past spring, but now we’re heading for a larger update to the latest version of Omeka. Thus far I have made a newer theme compatible with the latest version of Omeka that is also responsive.

Under the guidance of Dr. DeSpain and fellow members of the project, I’ve based the theme on a prototype design for the website along with the current version. Check out the comparison bellow:

I am not yet done with the theme. It is likely I will replace the blue-green book cover with a red one to tie it to the color scheme. I will also possibly add a subtle texture to the background. Still, look forward to that update sometime soon.

Exploring Nationality Through Landscape Illustrations

My research project, “Exploring Nationality in the Illustrations of Nineteenth-Century Transatlantic Landscapes as a Part of The Wide, Wide World Digital Edition,” is in full swing. The project, made possible through the URCA Associate program at SIUE, is working to analyze illustrations depicting landscape found throughout the more than 150 versions of The Wide, Wide World.

The illustrations and their placement in the text vary widely due to the novel’s publication during a time when there was no international copyright law between Britain and the United States. Publishers in both countries were free to alter the text and its illustrations with little to no restrictions, resulting in forty-seven sets of variant illustrations and over fifty different versions of the text. The illustrations include depictions of landscape ranging from pastoral ideal, such as the illustrations of Mr. Van Brunt tending his flock, which first appeared in an 1853 James Nisbet, Sampson Low, Hamilton, Adams, and Co. reprint (see below), to unkempt wilderness, such as the illustration of Ellen and Alice caught in a snow storm as they are searching for Captain Parry, which first appeared in an 1888 J. B. Lippincott Company reprint.

Throughout the project, I will be attempting to connect those representations to issues of nationality as I analyze the ways reprinters chose to portray and position the landscape, which will help to explain how segments of the population defined British and American identities between 1850 and 1950. Reprinters were aware that their readers would come from both Europe and the United States and that issues of nationality could not be ignored; the illustrations of landscapes they chose to include in their versions of the novel helped to define what it meant to be an American man, woman, Christian, and child. The illustrations depicting landscape also present an opportunity to analyze the impact of sentimentalism, broadly defined as the power of feelings to serve as a guide to moral conduct, as a political and cultural movement during the nineteenth century. Specifically, sentimentality becomes of great importance when looking at the illustrations of Alice and Ellen on the Cat’s Back as these particular illustrations pair the emotions of a distressed Ellen and the comforting presence of Alice with the open, sometimes rugged, often sublime landscape of the mountain. Emotion, and its ability to influence the reader, is here paired with the developing ideas of landscape in America, which helped to link the nation to ideas of emotional and spiritual awareness.

My work with the project is currently focusing on theories of nationality, landscape, and spatial relations, as well as working with the digitized versions of the illustrations to prepare them to be placed in galleries in the project’s Omeka site. This includes working extensively with Dublin Core, a controlled set of standards and vocabulary used on the website to describe each item, in order to provide thorough descriptions of each illustration. Once this step is completed, I will move on to analysis and to the creation of the galleries, which will include sub-galleries on watery expanses, American and British landscape, and character interactions in landscape. The sub-gallery on watery expanses will focus specifically on illustrations of ships crossing the ocean (see below), and the brook, a location made important through a scene in the novel that describes how Ellen attempts to cross and ultimately falls in after losing her balance, both of which become important when analyzing transatlantic relations. The sub-gallery on American and British landscapes will look at illustrations depicting landscapes from both countries in order to analyze the ways publishers from America and Britain were choosing to portray each nation; this will lead to conclusions about how each country was attempting to define and influence nationality, which will allow us to understand the development and refinement of nationality in America and Britain. The final sub-gallery will focus on illustrations that include representations of character’s interacting with each other and with the landscape. The movement and interaction of these characters will provide an opportunity to analyze the ways in which publishers were seeking to define Americans’ and Britons’ place in and development of nature.

Jennifer Roberts

Project Participant

URCA Associate

Personal Interface and Feminist Pedagogy, or What Jane Accomplishes Before Afternoon Tea

Jessica DeSpain’s article about the editorial collective of faculty and students who contribute to The Wide, Wide World Digital Edition was published this week in Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal. DeSpain particularly discusses the feminist underpinnings of the project and its work processes. To read more, visit: https://ojcs.siue.edu/ojs/index.php/polymath/article/view/2848.

Where We’ve Been, and Where We’re Going

In the summer of 2006, with graduate school funding from the University of Iowa, I began the first of many visits to special collections with the hope of completing my dissertation about transatlantic reprinting. The project, entitled Steaming Across the Pond, covered texts that were fraught sites of transatlantic debate because they were reprinted widely in both the United States and Britain. Before embarking on my trip, I read any novel, essay, or pamphlet that I could find in which characters crossed oceans both literally and metaphorically. I first picked up Warner’s The Wide, Wide World because it had come to my attention that Ellen Montgomery went to Scotland. Little did I know as I first held Jane Tompkins’s Feminist Press edition that this book would become my own little book history obsession.

In my travels to the Newberry in Chicago, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the British Library, and the National Library of Scotland, I found abridged copies, extended copies, copies with illustrations, and translated copies of Warner’s novel. In these depictions of The Wide, Wide World, I began to see a distinct evolution of national and gender identities taking shape over the hundred-year period in which the novel was printed.

The first version of the project, The Wide, Wide Hypermedia Archive, was a collection of the photographs that I took with my basic digital camera as I visited archives. It was rudimentary in its design, but my experiences with the first archive helped me develop a methodology for visualizing the material book digitally and how to encourage users to compare and interact with materials on the site.

The Wide, Wide World’s story is one of consistent repurposing and reimagining on the part of a plethora of textual agents with little to no concern for authorial authenticity or even first dibs. The Wide, Wide World’s adaptations are inherently collaborative and contain the work of illustrators, woodcutters, printers, and binders. Whereas we traditionally think of the work of the author as solitary, the printing house has always been understood as a collaborative space. The traditional work of a scholarly editor to choose one regularized reading text limits the influence of various textual agents and their productions–and, ultimately, works against the textual corpus itself. The multivocal revision sites of myriad editions and reprints resist a stable meaning actively and even symbolically.

My initial archive moved with me to Southern Illinois University Edwardsville in 2008, where my colleague Kristine Hildebrandt and I founded the Interdisciplinary Research and Informatics Scholarship (IRIS) Center. With support from internal grants and SIUE’s Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities (URCA) Program, I have been able to involve students directly in the labor and decision making that goes into the project.

2010-2011 project team from left to right: Consuella Kelly, Kelly Walsh, Jessica DeSpain, Brianne Foster, Kayla Hays

The project won an internal Seed Grant for Transitional and Exploratory Projects (STEP) in 2010 and a New Directions Grant in 2011, allowing us to borrow 82 versions of the novel from the Constitution Island Association in West Point, NY, which curates Warner’s home and papers. Working with an ATIZ book scanner, students and I spent five months scanning and renaming the books so that we would have over 10,000 high-quality archival images that would act as the data set for the site’s new iteration: The Wide, Wide World Digital Edition.

Our move toward a new version of the archive has also brought new collaborators to the project including Melissa White, a Visiting Assistant Professor at Alma College, who I first met because her extensive collection of copies of The Wide, Wide World took me to the University of Virginia; Bryan Dunlap, the lead archivist at the Constitution Island Association; Jennifer Brady, a Lecturer in the Committee on Degrees in History and Literature at Harvard University, who specializes in reader reception and Warner’s fan letters in particular; and Jill Anderson, an Assistant Professor at SIUE, who works on early American literature and the novels of the early national period.

This year, we have been establishing a standardized file renaming practice, preparing images for the web, developing our site design, and making our images machine-readable using Optical Character Recognition Software. We plan to use Omeka and Juxta to provide robust textual and visual comparisons of the novels variants.

On this blog the project team will record the development of the Edition and share what we learn with others in our quest to document The Wide, Wide World on the World Wide Web.

Jessica DeSpain

Lead Editor

The Wide, Wide World Digital Edition