Origin and Biography

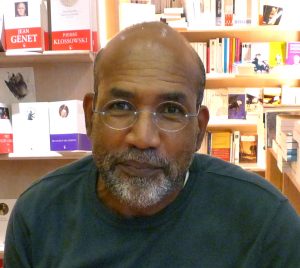

Patrick Chamoiseau is a French author from Martinique and was born in Fort-de-France in the year of 1953. Growing up, Chamoiseau was exposed to the Creole language and culture, it became a substantial part of the man (and writer) Chamoiseau came to be. Chamoiseau studied law in Paris and upon graduating, he initially did social work as a juvenile officer (Sheringham, 2013). It was not until later that Chamoiseau transitioned into a writer. He received a large amount of attention and achieved great success as a rhetorician. He had a major impact on literary theory and is best known for his novel Texaco which he wrote in 1991. Renowned for his work with Creole culture, Chamoiseau’s Texaco, can be best described as an ode to culture, language, and tradition. Chamoiseau tackles the sociocultural importance of Creole culture and globalization, using unique writing skills specific to his style. His writing, at its core, focuses on the oral significance of the Creole language and pursues an authentic representation of Creole culture. His writing in Texaco brings to light the complexity of multicultural realities that take place due to globalization. Chamoiseau writes in an intrinsically creative way. This might be seen best in his choosing to include himself as a character within the fictional story he chooses to depict. This tactic is rarely seen in fiction but is intentional by Chamoiseau and very effective.

Chamoiseau and Creole Culture

A question that many writers from the Caribbean try to answer is: “What does it mean to be Caribbean?” This question is the subject of a search for identity, and the word that Chamoiseau and his colleagues used to answer this question is “Creoleness”. Creoleness refers to how different cultures adapt and blend on islands or isolated areas (Sheringham, 2013). Chamoiseau’s writing reveals the beauty and individualism that Creole culture possesses, despite being under French rule, and how it is actively changing. In “Conquering City: The poetics of Possibility in Texaco” the author, Sarah Lincoln, states: “Creole culture, once the stronghold of Caribbean difference from its metropolitan rulers, and an imagined space of resistance to hegemonic (French) universalism, is being steadily eroded by the homogenizing forces of what Chamoiseau calls “City,” a force welcomed, as Texaco makes clear, by the very heirs of créolité itself and thus posing an increasingly intractable adversary for those who would resist its predations” (Lincoln 8). Lincoln dives into the complexity and nuance that “City” brings to the Creole culture in Martinique. We read Chamoiseau’s thoughts about the ever-shifting “City” in Texaco, and how Chamoiseau uses it to symbolize a multitude of different things like freedom, prosperity, and colonial power structures. In Chamoiseau’s style, he writes about “City” ambiguously and what it represents, readers will find this continues to change as the story progresses.

Chamoiseau Within Texaco

Chamoiseau’s writing style is unique in that his choice of wording is creative, his overall goal is to express this concept of Creoleness. His voice carries significance to a culture that is not often written or learned about, and his creative rhetoric leads the way for Caribbean literature. For example, he writes in the voice of protagonist Marie-Sophie Laborieux, “I’ve never gone there to see it myself, because you know, Chamoiseau, these stories about trees don’t interest me. If I tell you that it’s because you insist, in my appeal to the Christ on behalf of Texaco, I, Marie-Sophie Laborieux, was a little neater and the only reason I spoke was because I really had to, but if these things are to be written, I would have noted different glories than those you’re scribbling” (Chamoiseau 118). This quote accurately captures the creativity of Chamoiseau’s rhetoric because it reveals the many layers of his writing. He acknowledges himself within the reading of his existence by the fictional narrator, Marie-Sophie, that has been created. The narrator, Marie-Sophie recognizes that someone, Patrick Chamoiseau, is writing a story about her story, and notes that she “would have noted different glories than those you’re scribbling.” This idea of the author identifying himself through the narrator in which he voices carries significance because it reveals a reality about the fictional novel that didn’t exist within readers prior. By including himself as a character within his novel, Chamoiseau removes the gap between reality and fiction that once existed because Texaco is a fictional story. With this gap now removed, readers are more emotionally connected to the story created by Chamoiseau, and his writing can have a greater effect on his goal of representing French territories and Creole culture.

Creativity of Chamoiseau Revealed in Texaco

The creativity of Chamoiseau’s writing is illustrated throughout the book, especially when he writes notes from the narrator, Marie-Sophie’s journal. For example, in Texaco when the enslaved people had received their newfound freedom, Chamoiseau writes in a journal excerpt: “… even if the overseer no longer had a whip, he stood the same old way…. Notebook no 4 on Marie-Sophie Laborieux. Page 12. 1965. Schcelcher Library” (Chamoiseau 113). In this context, realism abounds within the text due to Chamoiseau intentionally including quotes from Marie-Sophie’s fictional notebook to give insight to the reader about the thoughts of her father Esternome. In a Los Angeles Times review, it was said: “As heroic as the tales of Marie-Sophie, her papa, Esternome, and mama, Idomenee, it is Chamoiseau’s chabin language that is the true heroine of ‘Texaco’. Marie-Sophie’s battles…are nothing less than the wars between French and Creole, between the classic and the patois, the colonizer and the colonized.” (Levi, 1997). The ending line about colonization is interesting as it compares French and Creole before comparing the colonizer to the colonized. Chamoiseau writes about the effects of slavery upon the people in the Caribbean before and after freedom in a way readers can easily connect to. Also, the relationship between father and daughter expressed within the created narrator who reads her personal journal carries an effect on readers that they can sympathize with.

Works Cited

Chamoiseau, Patrick. Texaco. Trans. Rose-Myriam Réjouis & Val Vinokurov. NY: Vintage, 1997.

Craddock, James. “Chamoiseau, Patrick.” Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., vol. 32, Gale, 2012, pp. 67-68.

Lincoln, Sarah L. “Conquering City: The Poetics of Possibility in Texaco.” Small Axe, vol. 15 no. 3, 2011, p. 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-1443259

Levi, Jonathan (2 March 1997). “The Enchantment of Language”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

Sheringham, O. (2013, January 7). From creolization to realization: An interview with Patrick Chamoiseau. IMI. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.migrationinstitute.org/imi-archive/news/from-creolization-to-realization-an-interview-with-patrick-chamoiseau

Editorial Collective

Dominik Kayser, LaRae Bigard, Megan Haug, Julia Nimmer, Anayah Lyons, Bailie Rabideau, Allison Rieser