In the novel Texaco by Patrick Chamoiseau, the concept of the Noutéka is invented to describe Esternome’s ideal community. In Esternome’s words, Noutéka is “a magical kind of we . . . [loaded] with the meaning of one fate for many,” (Chamoiseau 122). The idea of Noutéka is highlighted in the segment of Marie-Sophie’s notebook called “Noutéka of the Hills” from pages 123-132 of Chamoiseau’s novel. In this segment, Marie-Sophie describes the creation and maintenance of the community her father described, set apart from the land of the békés by a mountain. This Noutéka was unfortunately short-lived, as it was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Pelée.

Living with the Land

One component of Esternome’s ideal Noutéka that made him remember it fondly was the harmony between man and nature. This idea of living with the land stands in contrast to the békés’ method of stripping the land of nutrients with damaging crops. Marie-Sophie describes how food crops, considered “secondary crops” by the békés, were essential to the Noutéka’s goal of self-sustainability (Chamoiseau 128). An important part of farming was to raise medicinal plants with food crops and to mix up the type of crop in one place so the soil retains its nutrients. This method of gardening integrates traditional Creole techniques to maintain harmony with the land and keep life sustainable for the people dependent on it (Chavillon 323).

In contrast to popular belief, ecological romanticism was not the end goal of protecting the land in the way Esternome and his people are shown to. The people of the Noutéka, in addition to the indigenous peoples of North America and many others across the globe, promoted sustainable development and adaptability in nature’s ever-changing system. They were not afraid to change the land in ways they deemed necessary to make it suitable for development, but they cultivated an understanding of their environment’s limitations and planned accordingly (Smithers 268). While békés bent the land to their will with imported labor and imported materials to produce an ultimately exported crop, the people of Noutéka saw more instrumental value in claiming the land’s advantages as their own and benefitting directly from the fruit of their labor.

Community

An equally important aspect of surviving in the Noutéka was maintaining a sense of community. Esternome experienced a strong connection to his root identity, which originates from the ideas of memory and place. Memory ties into Esternome’s prized Noutéka, offering a common ancestral memory most directly reflected in Esternome’s fascination with Mentohs. Place relates to Esternome’s desire to assert a location as one for his people to take root in and claim as distinct from that of their oppressors (Chavillon 321). The novel establishes the importance of community through the formation of the Noutéka and how the people within thrived off interdependence. Esternome could not have created his gardens without Ninon, and Ninon could not have built her house without Esternome (Chamoiseau 135). Everyone in the Noutéka was reliant on one another, and this reliance made them strong. As Esternome recounted, “We carried our products on the heads of our women, the shoulders of our men, on the back of our donkeys . . . [because] helping each other was the law,” (Chamoiseau 130-31). Knowledge offered to the newcomers by the ones who learned through hardship created a community able to focus on refining their way of living and creating the best system possible.

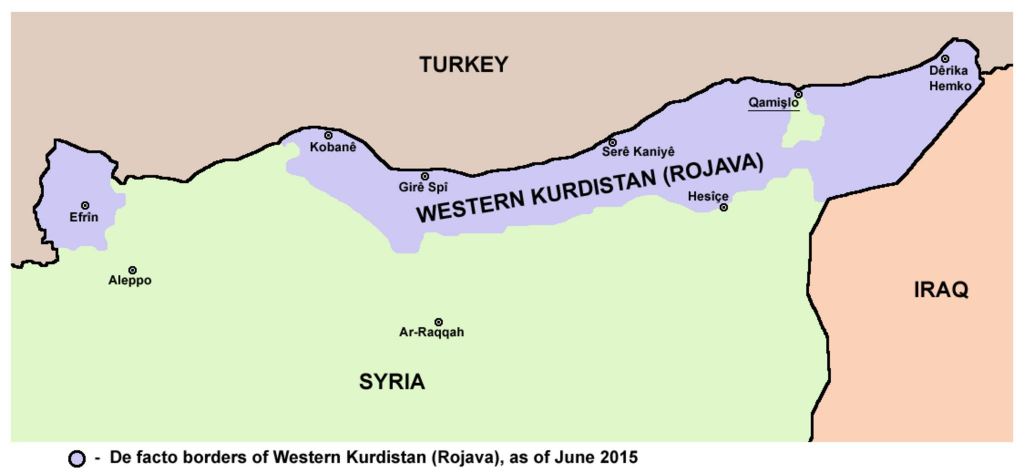

The system Rojava created is the modern-day political equivalent of Esternome’s ideal Noutéka. The community of Rojava holds a similar ideology to the one presented in Noutéka of the Hills if perhaps expanded a step further. Rojava was formed through a largely feminist movement to help Kurdish people escape their oppressors in Turkey. In Turkey they found themselves being severed from their ancestral homes through forced migration and assimilation (Lau 2016). This mirrors the capture and enslavement of Esternome’s people, which ripped away their autonomy and sense of cultural identity. In this way, Rojava’s formation reflects Noutéka’s. Rojava’s technique to give power back to their people was to rotate political positions often and create a truly participatory system. Communal government is not only maintained but enforced through the power of the people, and the people are the ones with decision-making power (Shahvisi 1007). Rojava reflects the values of Noutéka and may demonstrate what it could have become had it not crumbled under the combined weight of capitalism and natural disaster.

Decline of the Noutéka

The proclaimed Noutéka of the Hills did not survive long past its inception due to several factors. The most obvious factor is the eruption of Mount Pelée, which destroyed the Noutéka along with the entire city of St. Pierre. The Noutéka was already in decline prior to this deadly event. Factories appeared in the city below, and people left the Noutéka for many days of the week to work there. Even Ninon wanted to work at the factory (Chamoiseau 140). Ninon’s disappearance from Esternome’s life to chase her dreams with a musician ultimately mirrored the disappearance of his Noutéka too, which he would never be able to create again.

An Inspiration

Her Papa Esternome’s dream of recreating the Noutéka would influence Marie-Sophie. She was a wanderer like her Papa for much of her life, but once she got a taste of the elusive Noutéka, she chased it ceaselessly. She described the community she lived in just prior to her fight to establish Texaco as one with values mirroring her Esternome’s Noutéka, with people who cared about each other living in close harmony and supporting each other in their collective effort to survive (Chamoiseau 277). Her ultimate goal for Texaco was for it to become its own brand of Noutéka where people can band together under the magical we and care for each other in a way the residents of City never could.

Works Cited

Chamoiseau, Patrick. Texaco. Trans. Rose-Myriam Réjouis & Val Vinokurov. NY: Vintage, 1997.

Chivallon, Christine & Blair, Dorothy. (1997). Images of Creole Diversity and Spatiality: A Reading of Patrick Chamoiseau’s Texaco. Cultural Geographies – CULT GEOGR. 4. 318-336. 10.1177/147447409700400304.

Lau, Anna, Melanie Sirinathsingh, Erdelan Baran. “A Kurdish Response to Climate Change.” openDemocracy, 18 November 2016, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/kurdish-response-to-climate-change/.

Shahvisi, Arianne. “Beyond Orientalism: Exploring the Distinctive Feminism of Democratic Confederalism in Rojava.” Geopolitics, vol. 26, no. 4, July 2021, pp. 998–1022.

Smithers, Gregory D. “Native Ecologies: Environmental Lessons from Indigenous Histories.” History Teacher, vol. 52, no. 2, Feb. 2019, pp. 265–90.

Editorial Collective

Sage Biggers, Nikolai Careaga, Kayla Doerr