Introduction

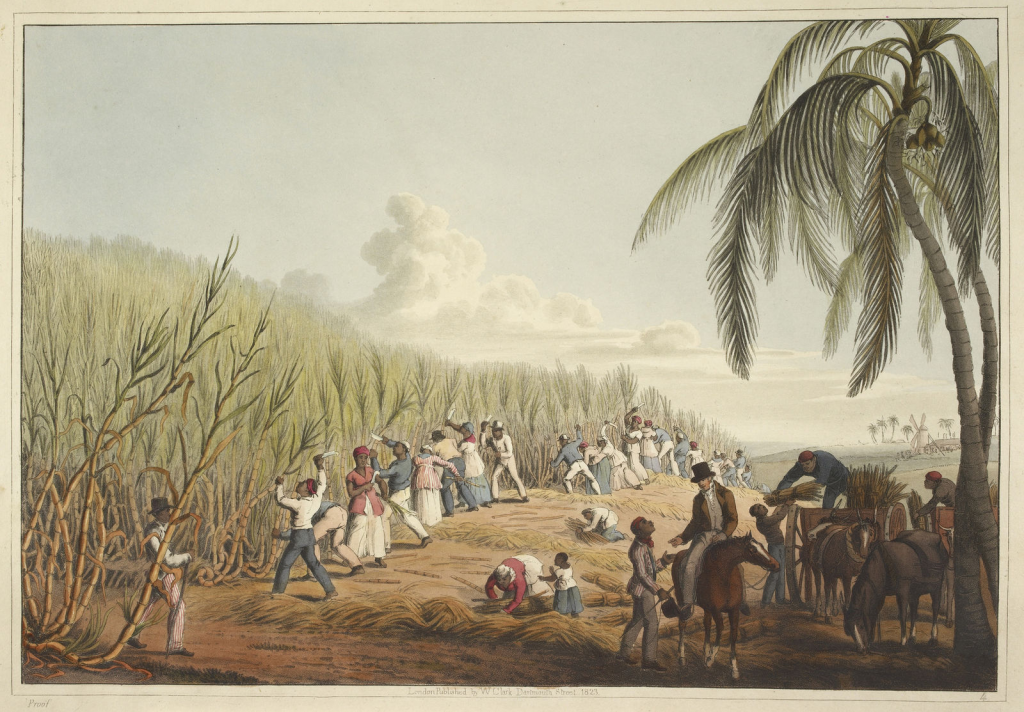

Békés are the white population of Martinique who have been living there for generations (Bongie 225). As seen with Esternome’s early life stories, békés were originally plantation owners and owned masses of enslaved people. The békés’ forces were harsh, and they continued to push the power discrepancies, which allowed themselves to continue to grow in power and wealth. Once slavery was abolished, the formerly enslaved still remained agricultural workers for the békés while being paid poorly. The citizenship that was gained did not give true freedom to these people as they were forced to work under harsh conditions and little pay. The people versus béké dynamic was not impacted too greatly as seen with Marie-Sophie’s experiences with békés. The hatred for békés stayed consistent, and she is seen fighting békés daily, which by the end of Texaco, békés are the ones in charge of businesses and companies and have a large impact on the local economy. The word béké is a more generalized term now for white business owners who have a lot of power and control.

In History

As seen in Texaco, békés are domineering authority figures who like to have all the power and enforce their prejudices. When the békés arrived in the Caribbean, they made up approximately 10-15 percent of the population in Martinique, and today, they make up about 1 percent (McCusker 221). While only being a small population, they aspired to preserve their race to guarantee economic authority through racial uniformity, so they enforced a caste to ensure white dominance. They would prevent interbreeding between races, and if there were to come a mixed-race child, they would refuse to recognize it (McCusker 221). Since starting as plantation owners, their idea that colored people were lesser and the hatred they harbored for them were made clear. These békés were seen as unjust and power-crazed owners. The control that the békés had made it harder for anyone else to succeed, and even the majority of Martinique’s laws were developed to benefit these békés to also ensure economic control and wealth (Bongie 224).

After hundreds of years of slavery, a free colored man named Cyrille Bissette became the advocate for freedom. He entered into an electoral alliance against a prominent béké, won in 1848, stirred the capitalist society, and played a major role in the Emancipation of 1848 (Bongie 225- 227). He is even known as the father of the abolition of slavery in Martinique (Bongie 224). Texaco showcases the celebration of citizenship and the hardships that shortly come after. Békés were still very haunting and cruel to the former enslaved people, and the hatred for békés never lessened. Some békés moved to neighboring lands in hopes to regain their force.

The békés that stayed, though, were resilient and shifted the economy from the plantation model to a “consumption driven import, tourist and service ” domination (McCusker 221-222). This way, the békés were still in power even without enslaved people. They knew how to exploit their power and forced their workers to work under abusive conditions and little pay. The workers were left with no choice other than to work to survive. It’s clear the wealth and control that these békés have has come from their past of slavery (Bongie 224). Martinique still has a power control issue and poor working conditions for many workers to this day, and many problems have surfaced but were not taken care of, which is further seen with Marie-Sophie’s struggles throughout life.

In Texaco

Throughout Texaco, békés are hated among the people of color due to their torturous behavior and unjust power. The narrator, Marie-Sophie, tells her story with her father, Esternome, who was originally an enslaved person living on a plantation owned by a béké. The békés during these early times were ferocious and corrupt, and even after the abolition of slavery, their ways didn’t change. It is explained that there were “two ways to work for a béké. The salary way,” which meant getting paid very little for each task, “Or the cooperative way,” which meant getting paid a share of the season’s harvest after the béké took his share, yet neither were “generous” (Chamoiseau 112). Both options didn’t allow the workers to live comfortably. The power hungry békés continued to use their cruel dominance for their own benefit, so strikes broke out, which gave the workers some more freedom against the békés.

Equality did not come with this freedom, however. Though some békés left the country, Esternome goes on to say that even without owning the workers, the béké “stood just the same old way” (Chamoiseau 113). They continued to abuse their power and carefully watched over the work that they were in charge of as if citizenship didn’t change anything. No government rules, strikes, or wars fix this imbalance and discrimination, and békés carry on controlling those around them. Over time, the term béké loosened up throughout the novel from purely the plantation owner to a more general term for business owners, and by the time Marie-Sophie is trying to make a city for herself, “béké” is often used for many of the white men who own businesses and have power.

Works Cited

Bongie, Chris. “A Street Named Bissette: Nostalgia, Memory, and the Cent-Cinquantenaire of the Abolition of Slavery in Martinique (1848-1998).” The South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 100 no. 1, 2001, p. 215-257.

Chamoiseau, Patrick. Texaco. Trans. Rose-Myriam Réjouis & Val Vinokurov. NY: Vintage, 1997.

McCusker, Maeve. “All Creoles Now? Béké Identity and Éloge de La Créolité.” Small axe : a journal of criticism 52 (2017): 220–232. Print.

Editorial Collective

Jayme Greer, Payton Carrol, Angel Flores