Language-External Context

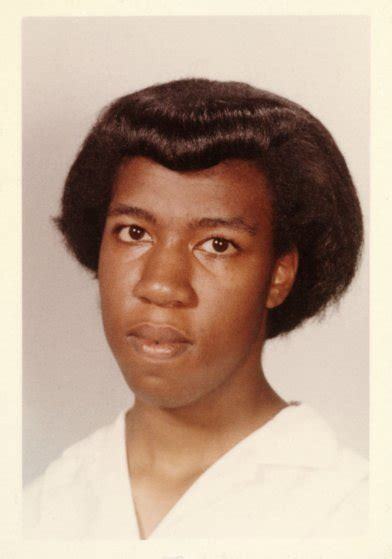

Early Life

Octavia Butler grew up the only child of a widow, also named Octavia Butler, who was forced to return to the workforce after the death of her husband. Butler was a shy child who was a voracious reader despite struggling with dyslexia. She was tall, clumsy, and not well liked at school and so, as many future writers do, she retreated to the world of books (Fox).

Butler was inspired to begin writing after viewing a poorly written science fiction movie entitled "Devil Girl From Mars." Realizing that she could certainly write something better, Butler began writing her own stories.

Butler's protagonists are almost exclusively African American women who are intelligent, well spoken, and trying to survive in hostile environments. Butler's characters speaking voices feature a remarkable lack of AAVE features, which reflect the way Butler herself speaks. We can hear Butler's rich, full bodied speaking voice in interviews recorded before her death, and she herself speaks with a lack of AAVE features, at least on camera. One can speculate that Butler's speech patterns reflect her growing up in multi-ethnic and integrated Pasadena, being a deep reader as well as an observer of human nature, and suffering from constant self conscious awareness. What I see is that Butler writes her characters both to reflect her own voice and to avoid them being stereotyped through speech. Working against the inherent prejudice against both women and people of color in science fiction, I believe Butler made a conscious choice to avoid any negatively stereotyped AAVE speech patterns of African Americans, or "typical" speech patterns of women so that her protagonists would not be misjudged as heroines in distress, but as characters standing on their own. However, her characters are abundantly aware that being African American makes their situations all the more precarious, and that they stand out as "the other."

Reception

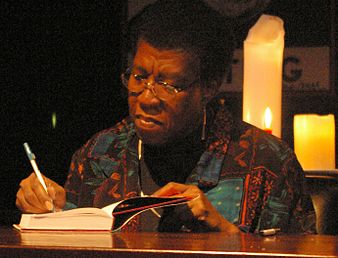

Octavia Butler's works have received wide acclaim in the African American community, as important contributions to Women's Literature, and in the world of academia. Her works have been incorporated into college level courses relating to African American literature and Black Studies as well as Women's Studies, and reviewed extensively as part of the Afrofuturism movement. She was awarded two Hugo Awards, two Nebula awards, and was the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the "genius grant," which she was awarded in 1995.

Because of the sudden nature of her death and the extensive body of her unpublished work, including notes, researched story ideas, and personal journals, The Octavia Butler Legacy Network was founded by Dr. Ayana AH Jamieson. The foundation is devoted to preserving and studying her works and their impact on current and future authors, and the organization has put together several events honoring Butler's legacy. Her works continue to be read and studied at panels, workshops, and celebrations (Hunt).

Dr. Jamieson noest that "Her legacy is larger than just herself or her individual work, more than anyone probably can imagine right now. She sort of dreamed things into being, the way our great-grandparents dreamed our liberation...And the social justice aspect of her work, or rather the way people use her work in social justice movements, is going to be at the forefront of whatever's happening, of whatever form the future takes" (Hunt).

Afrofuturism

First coined and defined by Mark Dery in 1994, Afrofuturism is "speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th-century technoculture — and more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future" (Dery). However, the roots of Afrofuturism can be traced back to various sources. such as the movie "Brother From Another Planet," released in 1984, and even further in the past to the works of musical groups like Sun-Ra and Parliament Funkadelic, whose tours featured elaborate stage acts with dancers and band members in metallic costumes, futuristic music, and, on occasion, spaceships, as seen in the video clip below:

What makes Afrofuturism unique is the placement of Black people, who have a long history of being suppressed, subject to violence or even genocidal acts, as not only still existing in futuristic settings that have long been the mainstay of white men, but performing as equals, in leading roles, as the hero or heroine, or even the majority rather than the minority.

"Afrofuturism, or what some call the Black Futurist Movement ... those things are needed in order to move us from the things that persist from the past that we are still engaged in overcoming,” says Ayana Jamieson, author, educator and founder of the Octavia Butler Network. "Undoubtedly, the writer’s name will always be inextricably tied to science fiction but it is now finding new life in Afrofuturism. The newish term and movement refer to a longstanding subgenre that imagines a future where Black and brown people and cultures are centered. Sometimes, Afrofuturist work features a resurgence of ancestral knowledge. Other times it’s woven with the high-tech trappings of mainstream sci-fi. Often, Afrofuturists blend the two"(Hunt).