An exhibit dedicated to the contributions of Americans during World War II

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/a_people_at_war/a_people_at_war.html

Content

This exhibit highlights the contributions of the thousands of Americans, both military and civilian, who served their country during World War II.

A People at war, introduction

The big idea of this exhibit is clearly and powerfully stated in the quote written above. This exhibit was made to highlight the contributions of American citizens during World War II (WWII). The main objective is not to focus on the heroes, the generals, or even the majority of people who served; but to highlight those whom history has all too often forgotten. While the exhibit does mention a few “big names,” such as General Eisenhower, the power of the exhibit lies in speaking for those whose voice has been lost.

The target audience, I would argue, is the American people in general. The writing is not overly complex, nor is there too much of it. The simplicity of the exhibit makes me think that anyone who knows how to click a mouse could access and appreciate what has been written here. I do think, however, that the American people are the target audience, because the entire exhibit is dedicated only to the contributions made by Americans in WWII.

While the writing is very brief throughout this exhibit, I do think a slight bias is clear. Of the twenty-five pages that make up this exhibit, nine are dedicated to racial or gender minorities who served in the war and nine more are dedicated to people/groups who greatly contributed but are seldom ever talked about when one learns about WWII.

The highlight of subaltern Americans who contributed to WWII has something new for everyone I think. Whether one learns about how Japanese-American soldiers only fought in the European theatre, or how the bombing of Pearl Harbor had been predicted as early as the 1920s; there is something new for everyone. This constant return and refocusing on subaltern history allows us as Americans and as Historians to greater respect and appreciate the sacrifices made by all those who fought under the stars and stripes.

Because of the “big idea” and how the exhibit goes about capturing it, I cannot help but argue how important its contribution is and should be for us. There were people and groups in this exhibit that I had never heard of, and yet without some of them the War could have had much different outcomes. For example, one section titled “Women Who Served” discussed the vital importance that female pilots had during the War; despite their forced status as non-combatants. The female pilots were largely responsible for transporting aircraft, soldiers, equipment, and scouting during WWII; without whose contributions the Allies surely would have suffered.

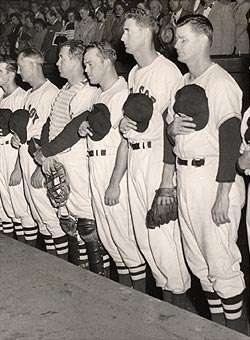

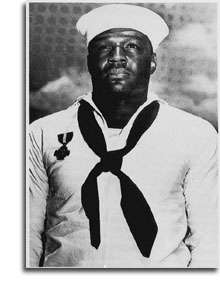

The exhibit approaches the topic of American contributions through three main methods. The earliest sections are dedicated to acknowledging those Americans who were racially different from the white Americans. The section “New Roles” is dedicated, in order: to General Benjamin O. Davis, the first black general in the United States military, the 99th Pursuit Squadron which was the first all black squadron to graduate from Tuskegee Field, the Navajo Codetalkers who were employed to keep secrets from the Japanese, and the 442md Infantry Regiment which was made up entirely of Japanese-Americans who fought in Europe.

The second approach to those Americans who greatly contributed to WWII highlights the women who served as non-combatants. The section titled “Women Who Served” highlights the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) and First Lt. Annie G. Fox who was on duty during the bombing of Pearl Harbor and was awarded the Purple Heart.

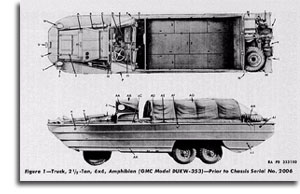

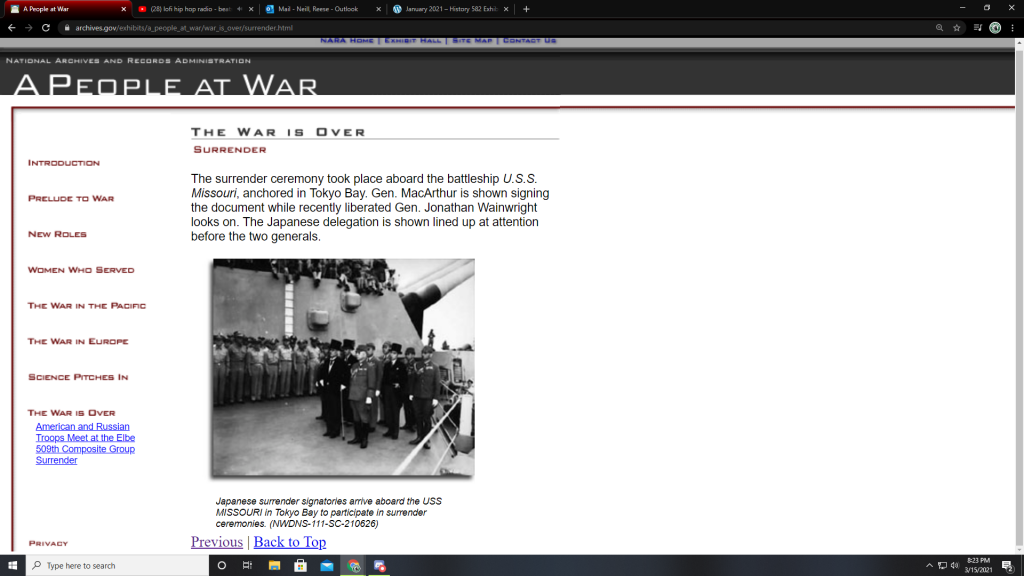

The final approach to the big idea is more traditional in that the exhibit dedicates the remaining pages to “The War in the Pacific,” “The War in Europe,” “Science Pitches In,” and “The War is Over.” In each of these sections the exhibit discusses a mixture of well-known information (such as the production and use of the atomic bombs) and unique, less well-known information (such as the production and use of the DUKW). The exhibit does, however, end on a page titled “Surrender” which very briefly discusses the surrender of the Japanese on board the U.S.S Missouri. This abrupt ending feels awkward and not in stride with how the exhibit began.

Methodology

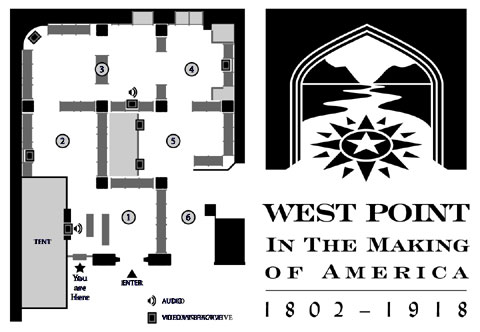

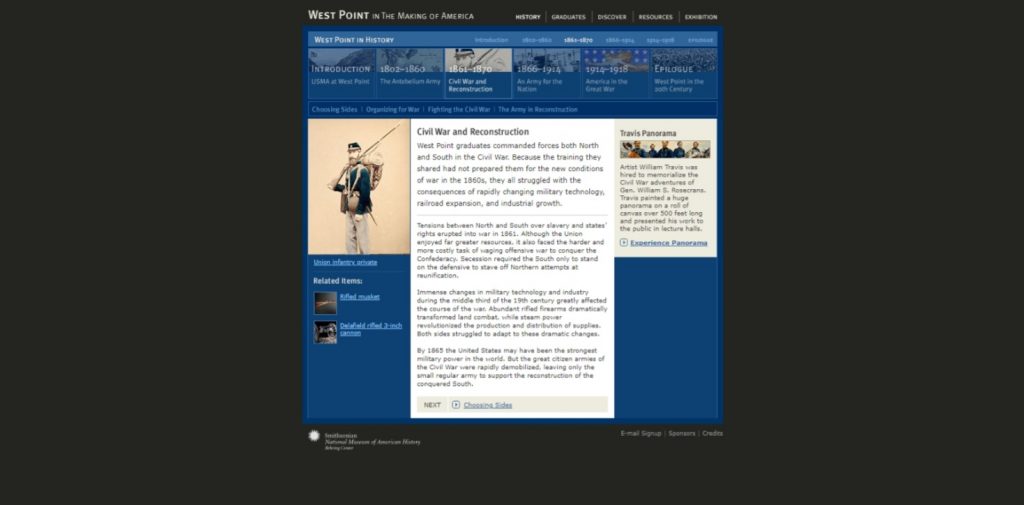

The website is accessed exclusively through use of hyperlinks along the left-hand side of the page. There are eight primary links which appear in red, and, when clicked, display individual title page links in blue. While this makes moving around the site rather simple, it does feel somewhat lacking in creativity.

Because of the use of hyperlinks along the side of the page the viewer is free to move about the exhibit as they wish. Clearly an order is suggested by the organization of the links, but no such is order is mandated by the website. My only qualm with the functionality of the site is that there is no “next” button which takes the viewer from one red topic to the next. Within one main topic, say “New Roles,” all the blue links and their pages can progress linearly with a “next” button at the bottom of the page. However, when you reach the final page in “New Roles” you must manually click on another red link to progress.

Design and Accessibility

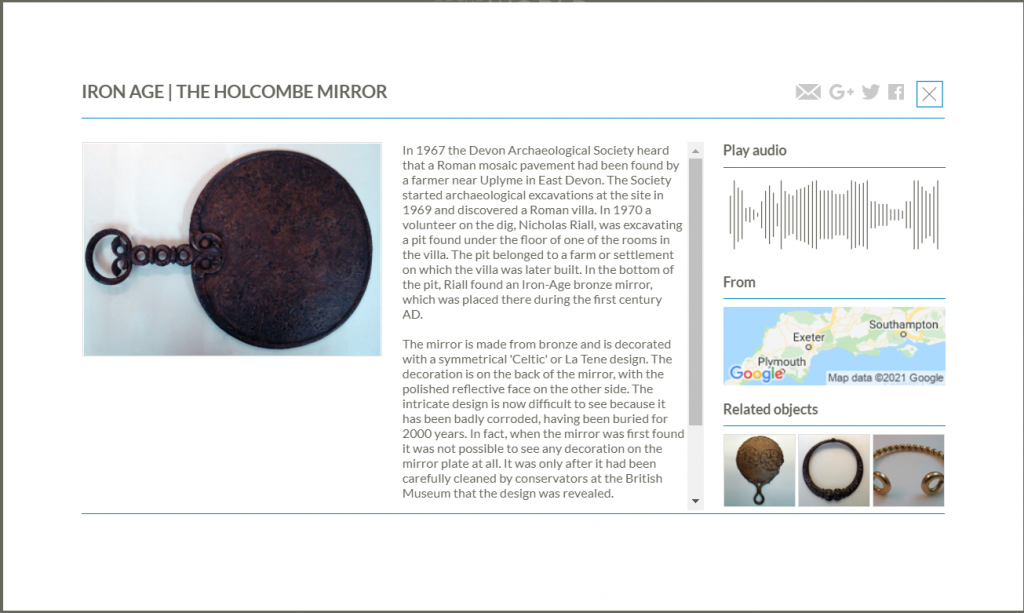

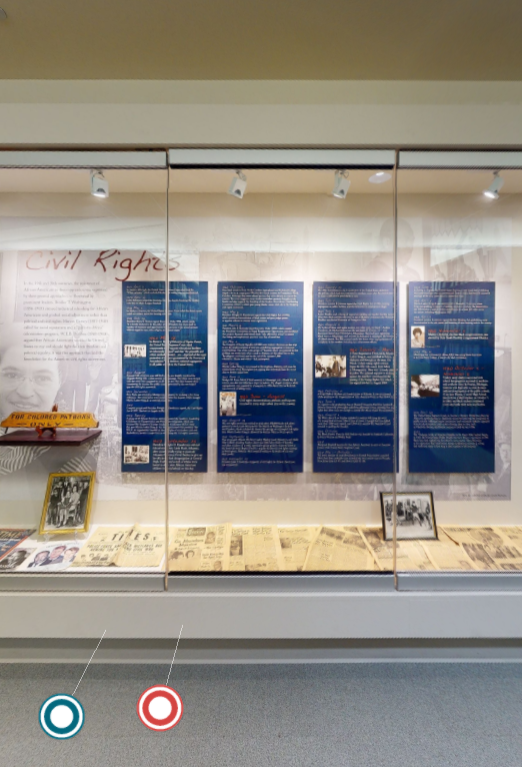

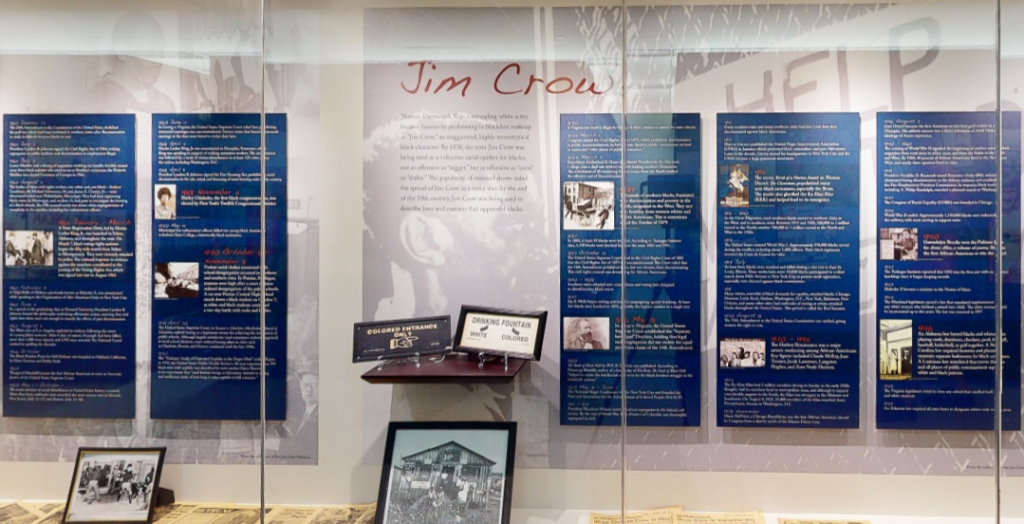

Of all the digital exhibits I have viewed thus far, this is the least engaging. There was limited text and even more limited visual stimulation. Each page did have at least one picture, to be fair, but there were no videos or “Tell me More” links. A select few primary documents were scanned and could be viewed, but otherwise the visual elements of the exhibit were painfully limited to small images.

The images themselves were well selected and did enhance the message of the exhibit, it is a shame that there were not more of them. The captions were explanatory of the images and did not offer much aside from that. It would have been very impactful to have a video or audio interview with someone who served during WWII in this exhibit. Hearing or seeing someone talk about these experiences would remind the viewer that they were not so long ago, and that the things discussed in this exhibit were real; they happened because of and to real people.

The color scheme and font is nothing to write home about. The pages of the exhibit remain on a white background and the body text is standard black color. The title of the pages is larger and possibly bold, it’s hard to tell based on the font, with the red subtitle beneath it. The main title of the exhibit, “A People at War” remains at the top of the page in white letters against a grey background. All of this font is easy to read and no colors clash or seem out of place.

The flaws of the design are fairly evident, however. The text and images only account for 1/3 of the screen, leaving far too much blank space. This makes the text and images appear small and rather insignificant. In addition, the lack of color or background imagery feels cold and distant, discouraging the reader from making the connection between the real people who this exhibit is dedicated to.

Final Thoughts

While the exhibit lacked flair and decoration, it did follow it’s big idea and did so well. This project could easily be expanded and follows an attractive pattern of new and unique history. It was refreshing to learn something new about this largely dissected time period, and yet was reassuring to see familiar names and events being talked about. The presentation of information in this exhibit is powerful, even if the design was lacking.