Haley Hammoud

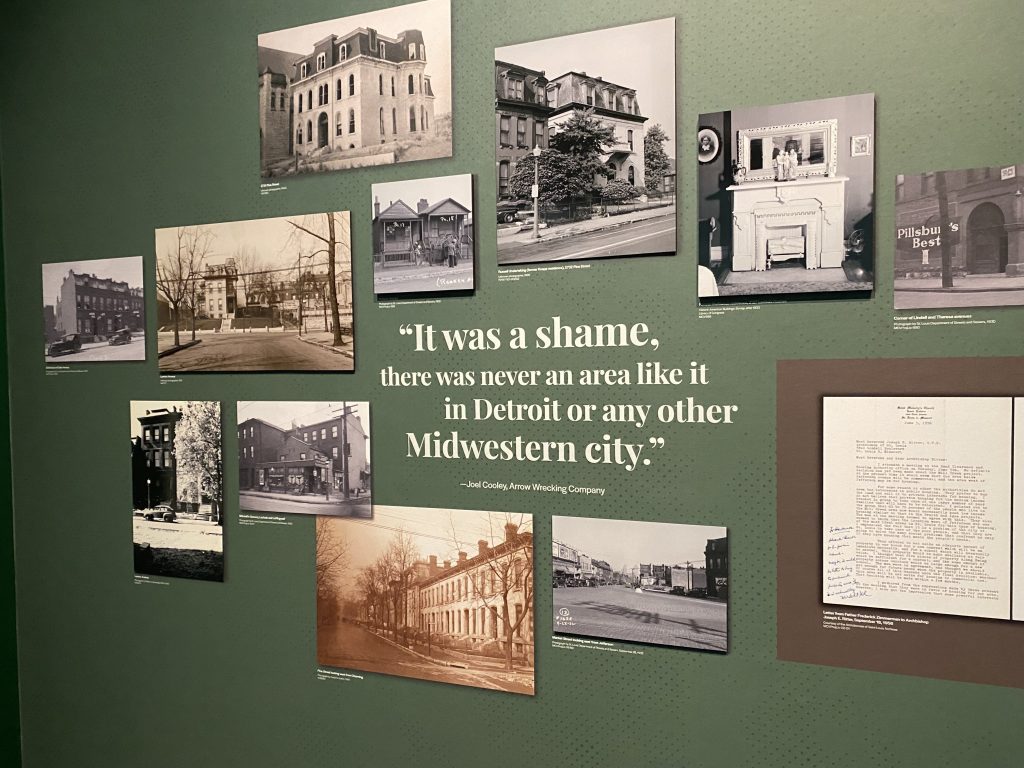

Mill Creek, a neighborhood that was once bordered by Grand Blvd, Olive St., 20th St., and the rail yard in downtown St. Louis, first belonged to the white elite before becoming an overwhelmingly black neighborhood during the Great Migration. In Mill Creek: Black Metropolis, a temporary exhibit at the Missouri History Museum, the Missouri Historical Society is shining a light on this once prospering community and its eventual demise in the name of urban renewal. Although Mill Creek was only one of few areas where black people could reside in St. Louis due to restrictive covenants, its residents took lemons and turned them into lemonade. This community bred successful businesses, schools, churches, hospitals, newspapers, sports and musical entertainment, and other important community-based institutions to address the needs of the city’s growing black population.

This exhibit counters the historical narrative that Mill Creek was a slum and that clearing it was a service to the city, arguing that it was, in fact, “a vibrant and proud community.” By demonstrating this, it brings an awareness to the city’s long history of institutional racism. It is no secret that downtown St. Louis has not exactly flourished in the decades since Mill Creek was razed in 1959. City government did not have immediate plans for the land other than to build an interstate highway, which only required the southern border, and rebuilding took a long time. The idea that 454 acres of bulldozed land was viewed as more beneficial to the city than a thriving black community…speaks for itself.

Gwen Moore, curator of urban landscape and community identity for the Missouri Historical Society, served as lead curator for the exhibit. Moore worked in conjunction with Vivian Gibson, best-selling author of The Last Children of Mill Creek, which was published in 2020, and other former residents whose stories are sprinkled throughout the exhibit. Visitors can find additional resources, Gibson’s memoir included, by visiting the museum’s website or scanning a QR code near the entrance to the exhibit.

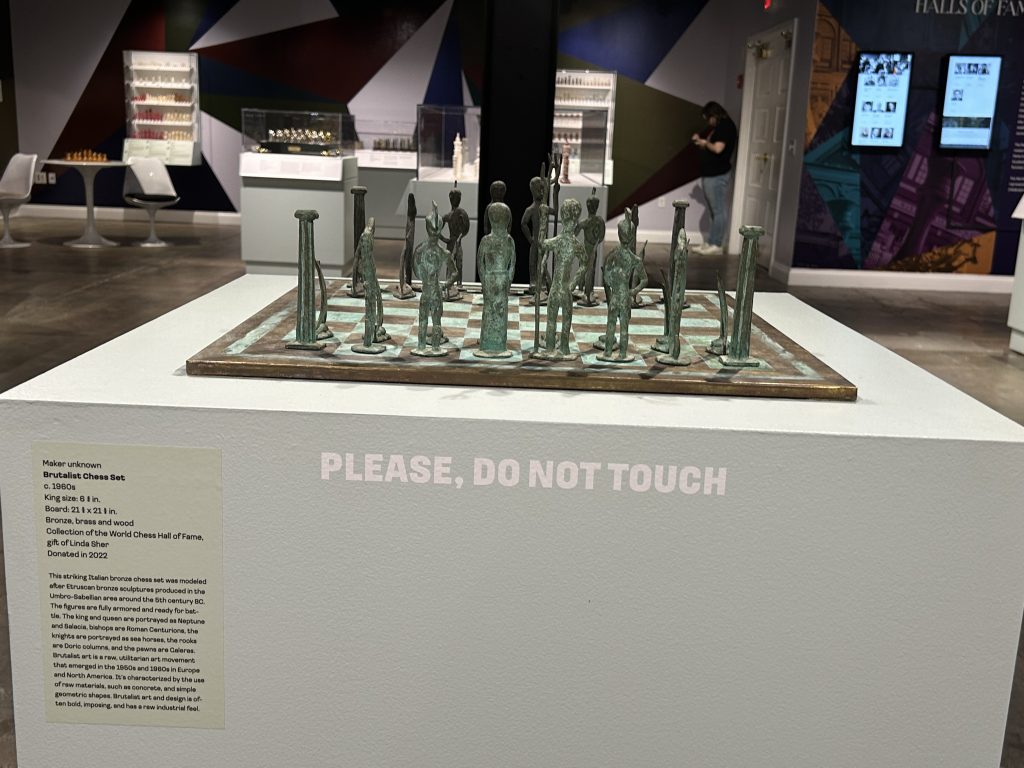

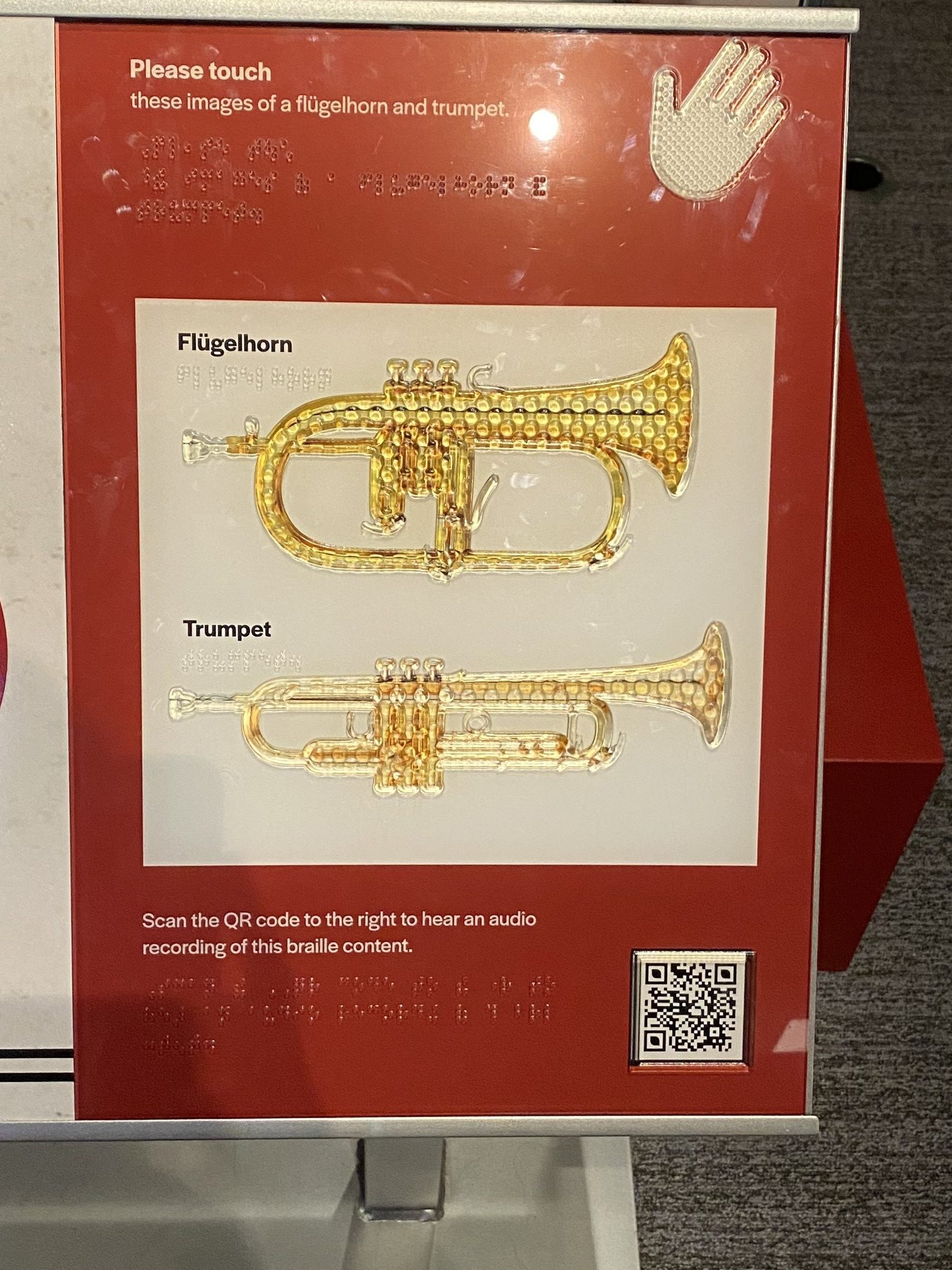

When I visited on the afternoon of February 8, 2026, there were many others present. Upon entering, I was confused about which direction to go because the exhibit has a shared entrance and exit, but soon I noticed the first section heading, which is marked with a number one. The exhibit contains five sections – Early Mill Creek, A City Within a City, We Are Mill Creek, The “Number One Eyesore”, and Impact and Legacy. Each section is numbered and introduced with a brief overview. The information is provided chronologically, beginning with the origins of Mill Creek and ending with the clearing of the neighborhood and the legacy left behind. Once a visitor knows where to begin, the flow of the exhibit is easy to follow, looping around in a big U-shape. The walkways are spacious, and overall, the exhibit is very accessible. There is an accessibility map just inside the entrance that details all the accessibility features offered. These include audio description for select objects via QR code, tactile elements with braille descriptions, and videos with captioning and ASL interpretation. The museum also offers a full audio tour of the exhibition.

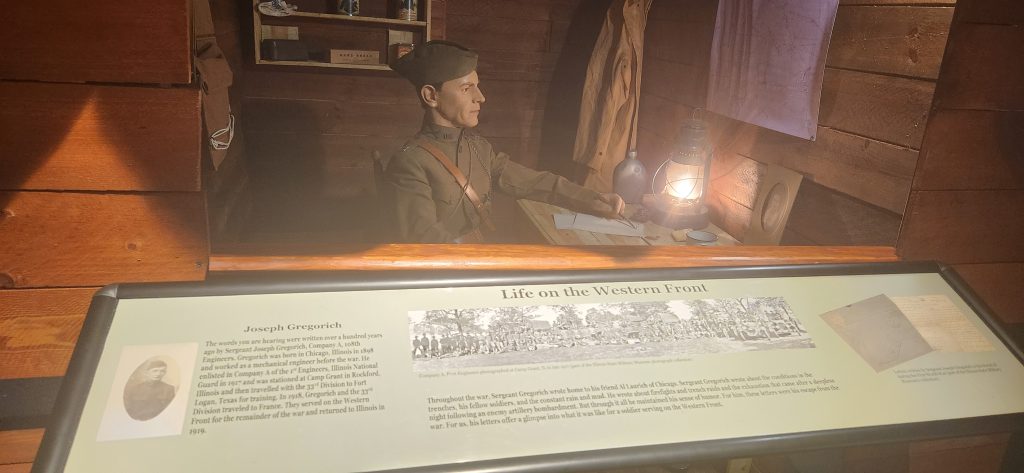

Although there are many other elements that help to keep visitors engaged, such as display objects, maps, videos, interactive components, bold colors, and pictures, the exhibit is very text heavy. There are several mid-size labels sprinkled throughout, which I consider sub-headings, and finally there are long panels underneath the display cases and photographs on the walls, which provide the most detailed information. To view it completely from beginning to end takes at least two hours (or more for those like me who are slow readers), and I found it challenging to reconcile my time constraint with my desire to read everything.

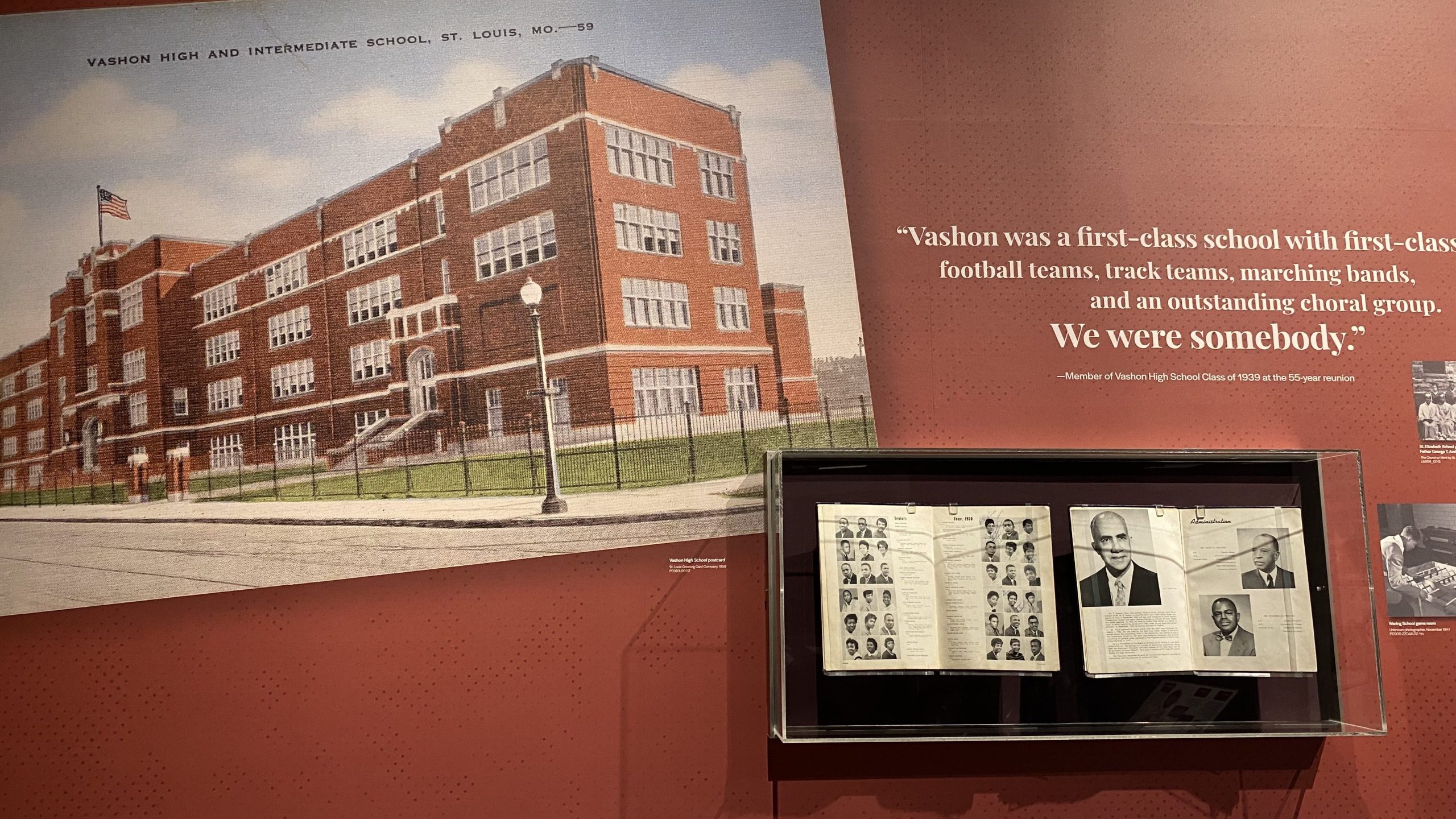

I felt a personal connection to the subject matter because the building in which I previously worked at Harris-Stowe State University is formerly Vashon High School and is one of very few Mill Creek buildings still standing today. Because of this experience, I was familiar with many of the locations referenced throughout the exhibit. Unfortunately, I was not aware of the history back then. It was not until last summer when I read Mid-Mod Mayor by Andrew Theising for a research project that I learned about Mill Creek. These personal factors increased my level of interest in the subject and made the viewing experience more enjoyable for me. Those less interested could probably get the gist by reading the main interpretive labels and watching the videos, but they would be forgoing the meat of the exhibit, which are all the personal stories. The exhibit makes its argument by amplifying the voices of former residents through interviews and primary sources.

Section two, A City Within a City, touches on different areas of everyday life and displays corresponding objects. Some that stood out to me were dental tools, an old baseball glove, and a stained-glass window. This part of the exhibit also contains a floor to ceiling screen that plays a silent reel of home movies, the images of people laughing and dancing together depicting black joy. Along with section three, We Are Mill Creek, which consists of images and personal stories of prominent Mill Creek residents, these sections serve to demonstrate that this community was just like any other. Given the current political climate, giving voice to marginalized groups and space for them to tell their stories is essential to combating prejudice. While poverty did exist in Mill Creek, it cannot be generalized as a slum. These were people from all walks of life living and working together to meet the needs of their community in the face of segregation and institutionalized racism in the city of St. Louis. Though Mill Creek was destroyed, this exhibit fights to ensure its legacy never will be.