On March 29th, I visited the Soldiers Memorial Military Museum and toured St. Louis in Service, the museum’s permanent exhibit. St. Louis in Service details the story of St. Louis and its citizens’ involvement in modern conflicts from pre-Revolutionary War to today.

The memorial is in Downtown St. Louis which does bring some issues for visitors. Parking can be very difficult, as the only official parking is street parking. While admission to the museum is free, you will have to pay for parking. Opened in 1938, the memorial features a cenotaph that is inscribed with the names of all the St. Louisans who died in World War One, as well as an incredible mosaic ceiling that honors Gold Star families. The museum is split into two wings with the memorial in the center.

The museum is split into two wings with the memorial in the center.

Upon entering the East Wing I was greeted by an incredibly helpful attendant who told me the layout of each wing. The Revolutionary War to World War I is featured in the East gallery, while the West gallery features World War Two to the present. You can theoretically view the galleries in any way you want, but I decided to view them chronologically and started in the East gallery.

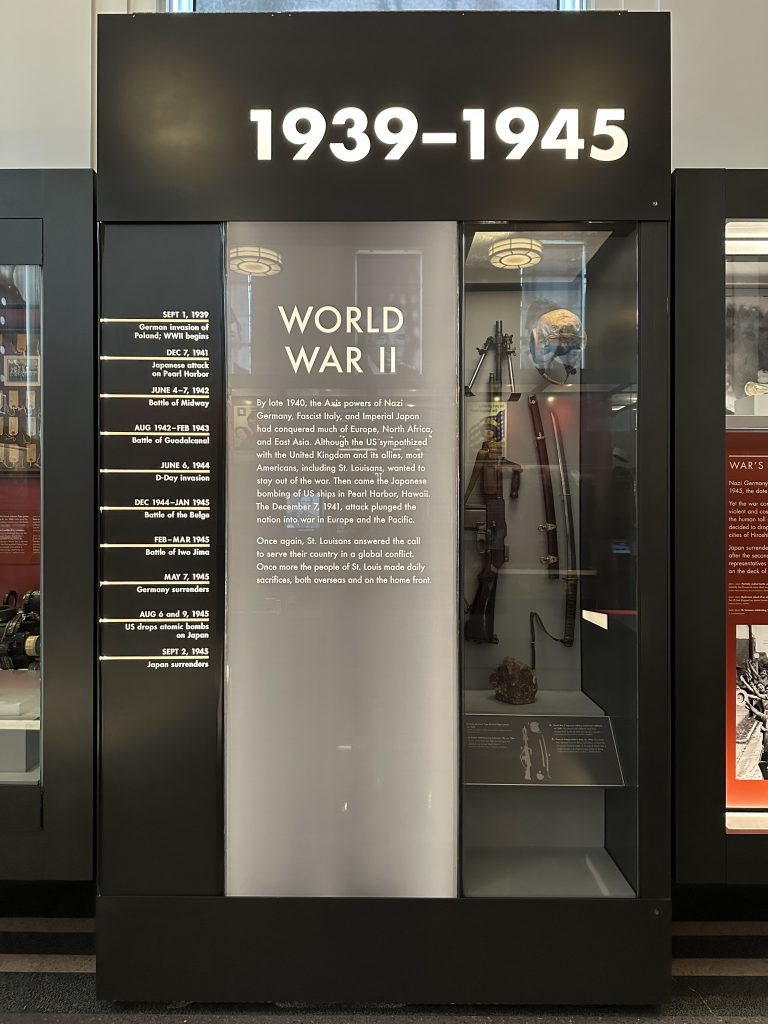

Both galleries have a very similar layout with each end having a large timeline that displays the events and period covered by that side of the gallery, as well as a center section with a special display. The galleries flow in a counterclockwise direction around the center display, but visitors can view it in any way they please if they are not interested in chronological learning.

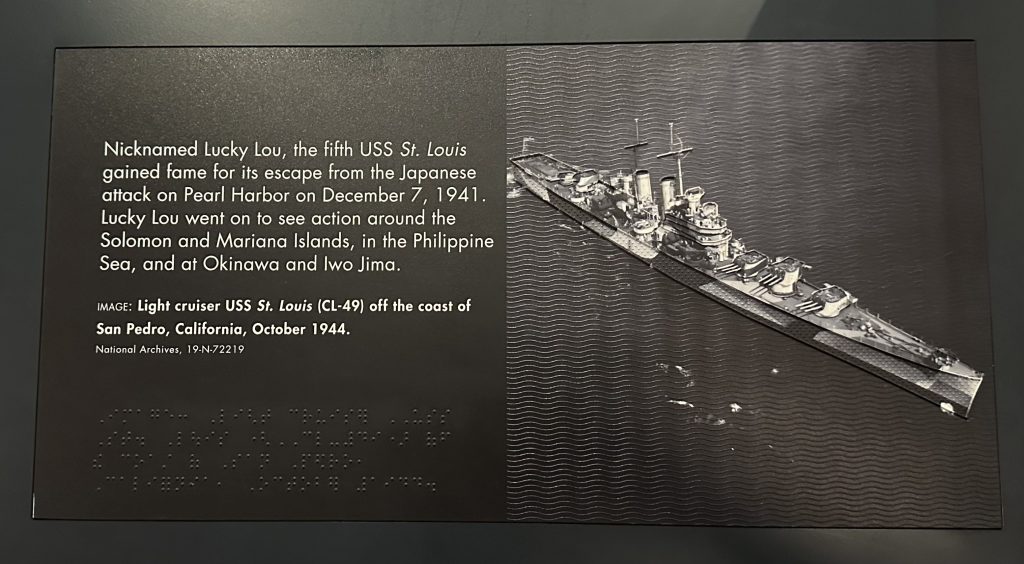

The right section of the East gallery covers 1750 to 1900, while the left section is from 1914 to 1918. The center display of the East gallery features a bell from the USS St. Louis, a protected cruiser used in WWI. This section discusses the history of all seven ships that have carried the name USS St. Louis. It also details the meaning behind the four large statues that adorn the outside of the memorial and has small, touchable models of each. In the West gallery, the right side discusses 1939 to 1945, while the left covers 1947 to today. The center is a display of modern uniforms from every branch of the military, as well as changing pictures of soldiers from St. Louis and two interactive touch screens that allow you to sort through the names and stories of other soldiers from St. Louis.

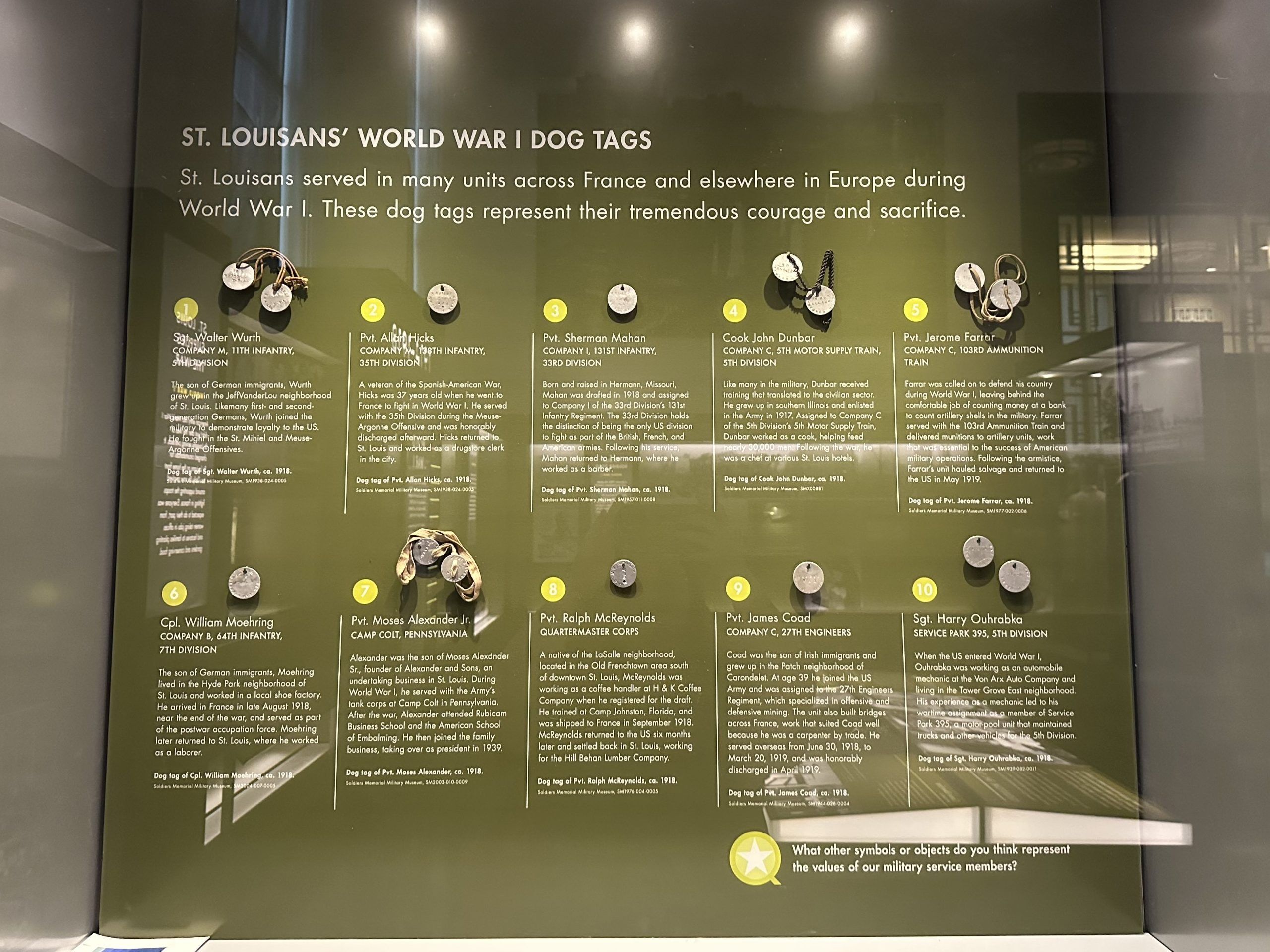

The artifacts, while all related to the military, have quite an incredible range. From something as small as a pocket Virgin Mary figure carried by a man in WWI to something as large as a WWII aircraft gun turret made by local company Emerson Electric, it is a magnificent collection. The text that accompanied each artifact helped bring them to life and told an excellent story. Some of my favorites were the WWI dog tags that told a brief story of each man they had once belonged to.

The interactives were perhaps my favorite part of the exhibit. They had large touchscreens where visitors could play games, go through items in the collection, and even listen to oral histories. These features add a new layer of learning and are incredibly helpful. My favorite interactive was in the East gallery which allowed visitors to design their own Iron Clad ship. The interactive allowed you to choose hull shape, gun deck type, armor, propulsion, and armament. After you completed your selections, it would walk you through a series of tests that would determine if your Iron-Clad ship design was successful or not. This helped me to understand how these ships worked and how they were useful during the Civil War.

The majority of the readily available accessibility features were braille signage and images throughout the exhibit. They also have audio descriptions available through their website. The galleries are both quite accessible with everything being spaced out well. There were a few issues I saw with accessibility in the exhibit. First, the galleries were both quite dark. The cases and text were well-lit, but navigating darker spaces may be challenging for some. Another thing is that some of the cases and text were too high and might be difficult for someone in a wheelchair to read.

One thing that I could not find in the exhibit was any information on who the curator was or any form of bibliography. I may have received this information from the front desk but I did not think to ask at the moment.

I think the exhibit did an excellent job of presenting the stories of everyday St. Louisans to help show audiences how St. Louis, a city far from most battlefields, is deeply rooted in military history. They focused on stories of people from all different backgrounds, not just what people would find the most shocking or interesting. My main complaint was that the galleries were quite dark, but in historic buildings like that, it is often difficult to get good lighting. I believe this exhibit is excellent for anyone and would be easily understood by people with very little war knowledge.