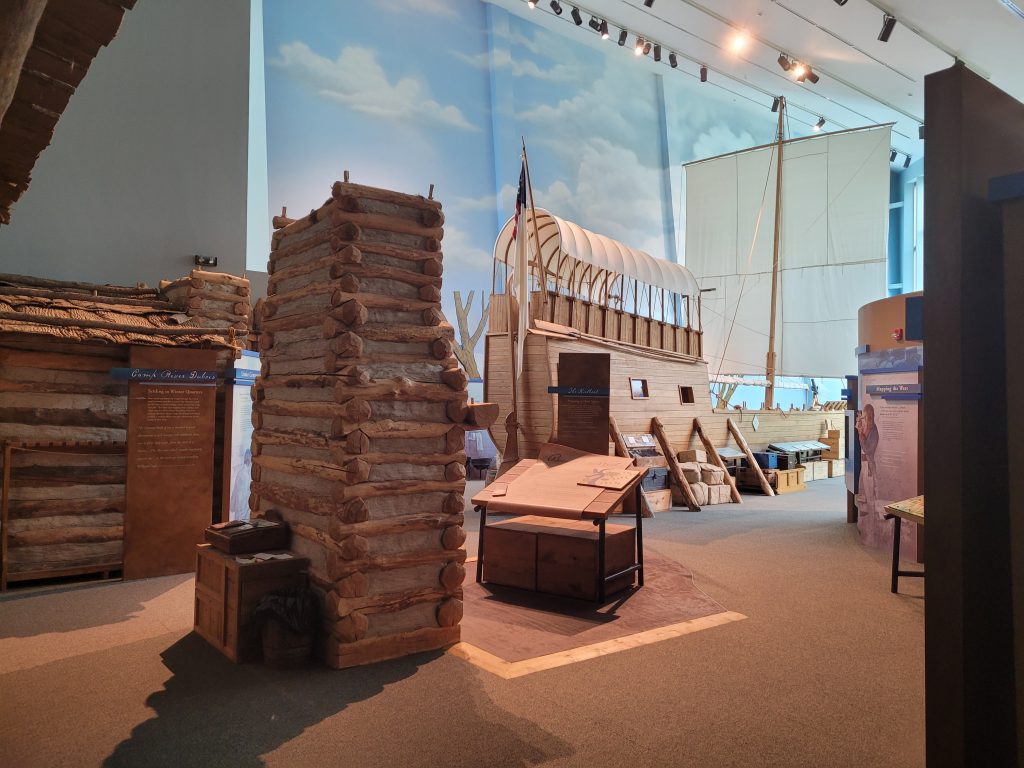

Walking into the exhibit space at the Lewis and Clark State Historic Site evokes images of a child’s imagination or a still image from an early 2000’s TV program. Bright blues and three-dimensional arrays cascade along a wall dedicated to the lives of Lewis and Clark, with a bronze statue serving as the focal point for the entrance. After walking through a section relaying the trade artifacts, outlining the various tribes interacted with, and the general goals of the early explorers of America, one is greeted by a tremendous spectacle: half of a wooden vessel parked in the center of a hall of wooden items. This is a model of the boat used by Lewis and Clark on their expedition to the Pacific.

This model spans most of the area it resides in, along with filling about a quarter of the horizontal space available. This ship is bisected as well, allowing one to see the inside of the ship and how certain items and provisions would be stored. For example, there are sections of bisected barrels that show the inside containing salted pork, trade items, and even alcohol that would have served to keep the crew alive. As one traverses from the back of the boat towards the front, on their left is the exterior of the boat if they walked down the right side of the boat from the back, with further panels and items expanding upon the tools, lifestyle, and future of the unit. If one were to walk on the left, they would be informed about various aspects of woodworking, trade, and the scientific discoveries made by the Lewis and Clark group during their adventure.

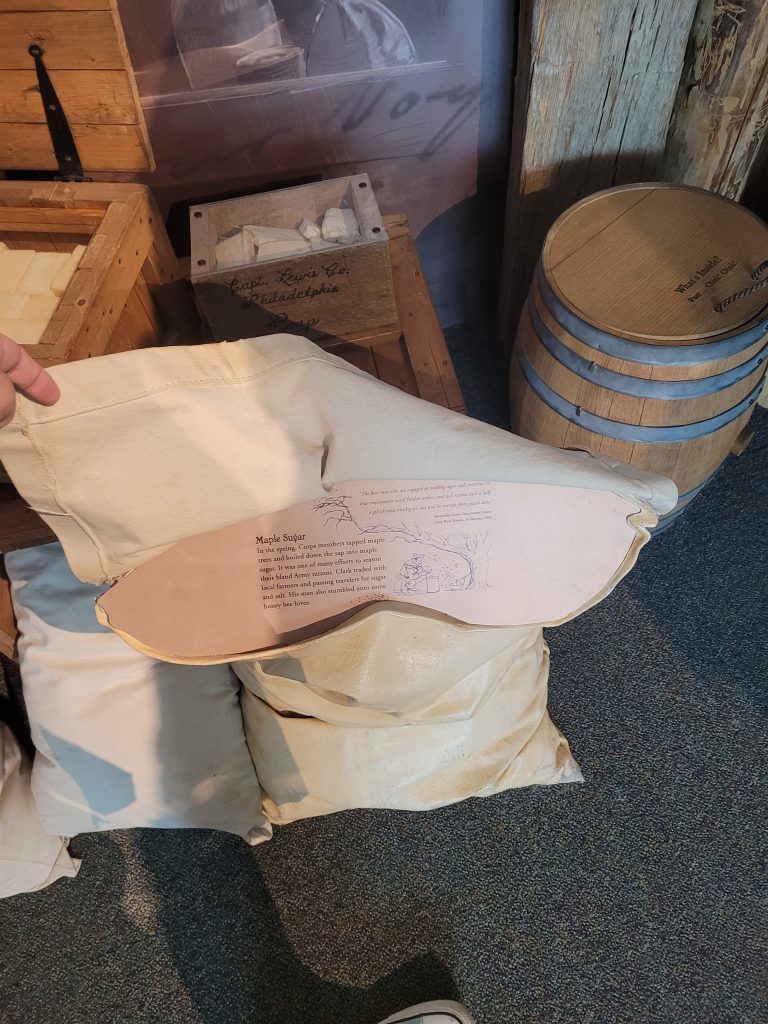

This exhibit showed many different facets of the expedition, but it also showed light upon lesser-known facts of the crew and adventure, such as how the language was translated from English all the way to the specific tribal language spoken where they traveled. In addition, this exhibit was heavily interactive with various stamp stations which would engage children to find various objects or trace certain lines on a map, but it also had interactive physical elements, such as a flap on a cloth bag that would give information within.

This exhibit featured an extensive use of three-dimensional learning aids with an appropriate amount of text for both children and adults. However, this exhibit did not have any sort of reading aids for those that may be visually impaired. This museum did feature a comprehensive design for those that are wheelchair-bound or mobility impaired, as the floor plan was open, flat, and featured ramps that lead from lower to higher areas. In addition to this, there was a linear mapping for the exhibit, which went from a timeline and introduction to essential information, then an optional movie, and then the final major exhibit: the boat. After this was a small closing section that discussed the aftermath of the expedition and a small display case that had an accompanying legend of the items.

Overall, this museum is one that is easily accessible, child friendly, and also stimulating with its array of displays and physical items. There may have been a slight slant in the story-telling, as it is a historic site dedicated to Lewis and Clark, but it also allowed some smaller details that usually aren’t highlighted to shine. This boat exhibit is one of the most exciting I’ve seen and it is still an enjoyable experience, regardless of age or knowledge.