The Illinois Military Museum, located on Camp Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, houses the state’s Military history, focusing primarily on the long Illinois Militia and National Guard history, but also covering military service by Illinois residents across multiple conflicts, from Indian Wars to Afghanistan and Iraq. While its most famous relic is not on display, Santa Ana’s wooden leg, the museum is a place worth visiting for an enjoyable afternoon.

Your visit to the Museum starts with outdoor displays of various military equipment, most notably an AH-1S Cobra and UH-1H Huey Helicopters, as well as some tanks and other equipment. Part of the Museum’s outdoor static display is located at the entrance to Camp Lincoln and are inaccessible up close to the general public.

The museum itself is housed in the oldest building on Camp Lincoln, the 1903 Commissary building, built in the Romanesque style of architecture and reminiscent of a castle. The first floor has a small admissions/gift shop area, a flex space for events, restrooms and access to the vault (not open to the public), as well as a few small displays. The main viewing gallery, however, is located on the second floor, accessible by stairs or elevator.

Laid out in a directed path and generally chronologically, though you must past through some of the more recent actions (Iraq and Afghanistan) to reach the oldest history from the Mexican American War and establishment of Illinois Militia Regiments (predating the Illinois National Guard). Swords, sabers, rank, medals, hats and uniforms from this period are on display inside cases. Exhibit signs, although typewritten on simple parchment paper, are informative and discuss the Militia’s transformation to the Illinois National Guard, starting with the Milita Act in 1903 that provided federal funding for equipment and training and began the process of standardization for the fully integrated National Guard of today.

Also included in this early period of the Illinois Milita is a detailed model of Fort Dearborn, started in 1803 at the confluence of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan (now the City of Chicago). The model details the Fort on the eve of the War of 1812, just preceding the Fort Dearborn massacre by Pottawatomi Indians allied with the British.

Model of Fort Dearborn, Cir 1812

From here, the Museum pivots to an in-depth look at the civil war and includes multiple artifacts from both sides of the conflict. On display are just a couple of the extensive flag collection the museum maintains from this and other eras. These flag displays are rotated to help preserve the fragile material.

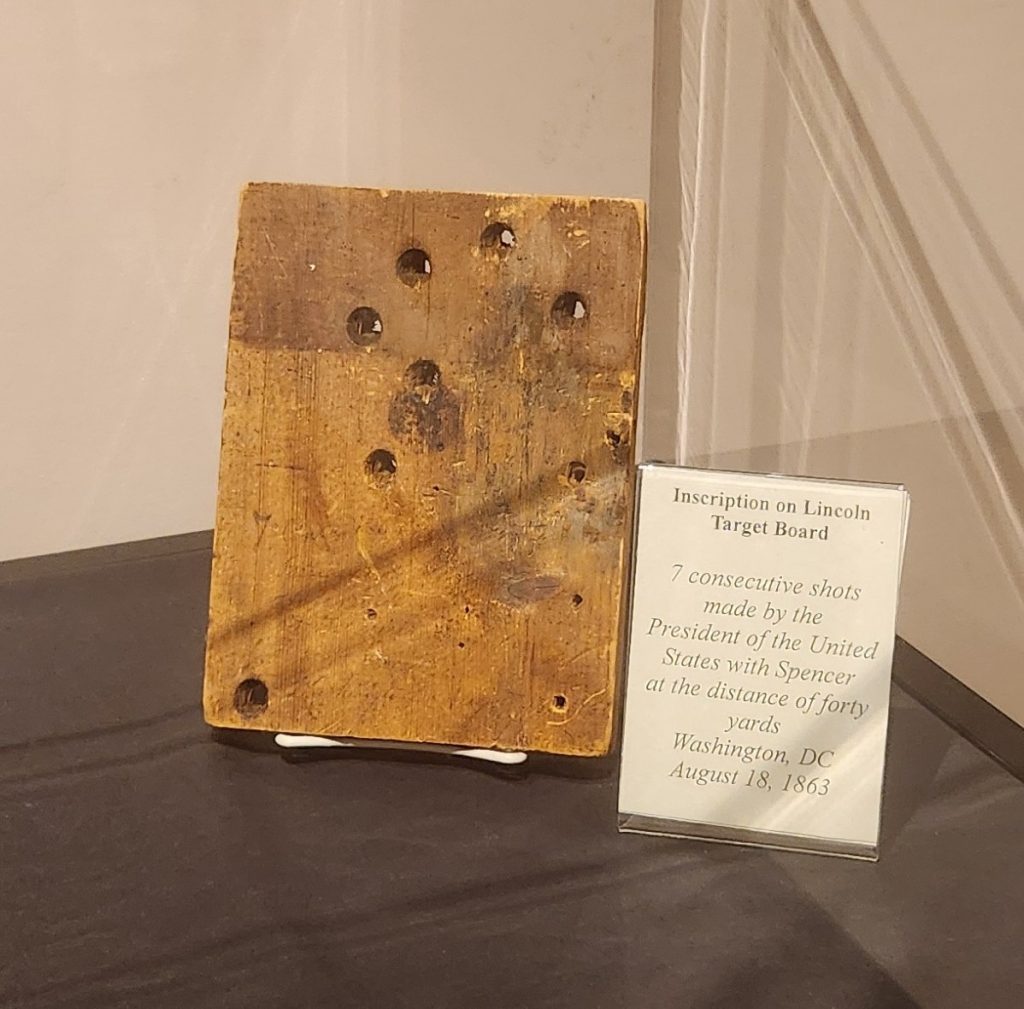

Abraham Lincoln’s Target Board for the Spencer Rifle ^

<Tree trunk from the Battle of Chickamauga

This area of the museum also includes two of the more unique exhibits, one of a preserved tree trunk with artillery shell fragments imbedded from the Battle of Chickamauga, and the Target board with 7 shots made by President Lincoln with the Spencer Repeating Rifle (an example which is also included in the display) which was later acquired for use by the Union Army.

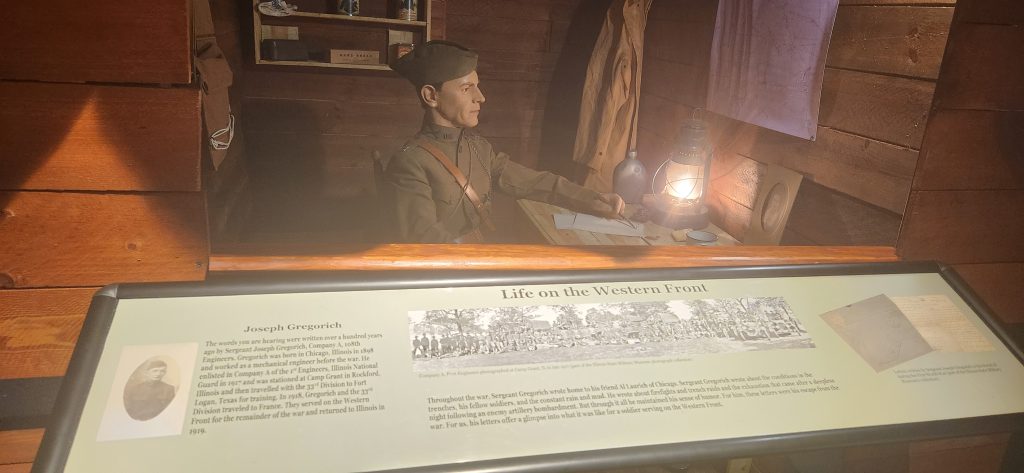

From here, the museum covers conflicts from the Mexican-American War, World War I (including an interesting audio preservation from inside a WWI Bunker), WWII, the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In this portion of the museum, the exhibits include highly developed dioramas with professional labeling, high-lighting units and individual accomplishments.

World War I Trench Diorama

This flows into the more modern era, including not only Desert Storm, but also Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. This section also details the National Guard’s support to domestic operations, unique among the armed services, such as during the Great Flood of 1993, Covid and other domestic operations.

Previous Exhibit of Santa Ana’s Leg, no Longer on Display <^

As mentioned, the museum’s most famous exhibit, Santa Anna’s wooden leg, taken by 4th Regiment Illinois Volunteers Militia members during the route of the Mexican Army in the Mexican-American War during the battle of Cerro Gordo in 1847, is not on display and has not been for some time. According to museum volunteers, the leg had been on continuous display for decades and it is in severe need of conservation.

Though federally and state supported, the museum still lacks the resources to complete this conservation so the leg sits in climate-controlled storage (along with approximately 80 percent of the museum’s collection), awaiting the day it can be restored and put back on display. In the meanwhile, there is no indication that this relic of history exists in the museum. A short presentation, picture and description along with an “this exhibit is undergoing restoration” would help to keep this story alive and help console visitors disappointed with not being able to see this unique part of Illinois military history. Still, there is plenty to see in the rest of the museum, which is well worth the trip.

The address listed is 1301 N. MacArthur Boulevard, which is actually Camp Lincoln, headquarters for the Illinois National Guard, but access to the museum is not through Camp Lincoln’s main gate. Instead, continue north on MacArthur past the main gate approximately 1,000 feet to get to the Museum’s own entrance. The museum is open Tuesday-Friday 1-4:30 pm and Saturday 9-12 and 1-4:30. Admission is free; however they do accept donations.

The museum also participates in the Explorer Passport as one of 12 Abe’s (Abraham Lincoln) Hat Hunt Sticker Stops throughout the Springfield area. For more information on the Illinois State Military Museum visit their website at https://militaryaffairs.illinois.gov/ilmilitarymuseum.html. You can also see more about Abe’s Hat Hunt on the Visit Springfield Illinois website at https://www.visitspringfieldillinois.com/Landing/AbesHatHunt.aspx.