SLAM Arts of Asia: Chinese Galleries

As someone who has grown up visiting SLAM, I wanted to try and have a new, organic experience for this summer’s visit to Art Hill. I set out alone on Sunday, June 26 with the goal of seeing a SLAM gallery in a new light. Visiting alone was the first step in that direction, I think – visiting a museum is often a social exercise, as we’ve learned throughout our Museum Studies coursework. Of course, the St. Louis Art Museum – and Forest Park in general – were popular destinations for St. Louisans on that Sunday. Two greeters were handing out maps at the entrance. I gave them a smile and walked by – though I’m usually one to take home all program literature offered at a museum, I had the express goal of allowing my feet to lead the way. I meandered by the informational desk and turned right at the furthest entrance from the front doors, finding myself at the entryway of the Asian Arts exhibits. Two docents paced the length of the gallery, and a few guests drifted past the cases. I decided to commit to my “no-plan” plan, and set about defining the parameters of my review.

Because each regional section at SLAM is so broad, I quickly decided to focus my review on the jade/bronze/Buddhist sections of the Asian Arts exhibit. These three rooms – the Bakewell Gallery and two square “crossroads” spaces within the Asian Arts galleries – are the subjects of this review. Focusing in on this “sample size” exhibit not only allowed me to better analyze the physical space, it also provided a way for me to situate this exhibit within the wider scope of Asian Arts as a whole.

The overarching “big idea” for this exhibit is the tracing of Chinese cultural and religious practices from prehistoric times through the beginnings of Buddhism through three-dimensional jade, bronze, and even ceramic artifacts. Based on my experience during this visit, I felt that the exhibit did successfully communicate the “big idea” through the use of chronological organization, types of objects highlighted, and a clearly intentional use of space.

Cases of objects lined the walls of the gallery in typical SLAM style, with objects organized by material (per case) and chronologically (as one moves through the gallery), visually culminating in a large, polychrome sculpture at the end of the hall, framed by a large doorframe with crown moulding.

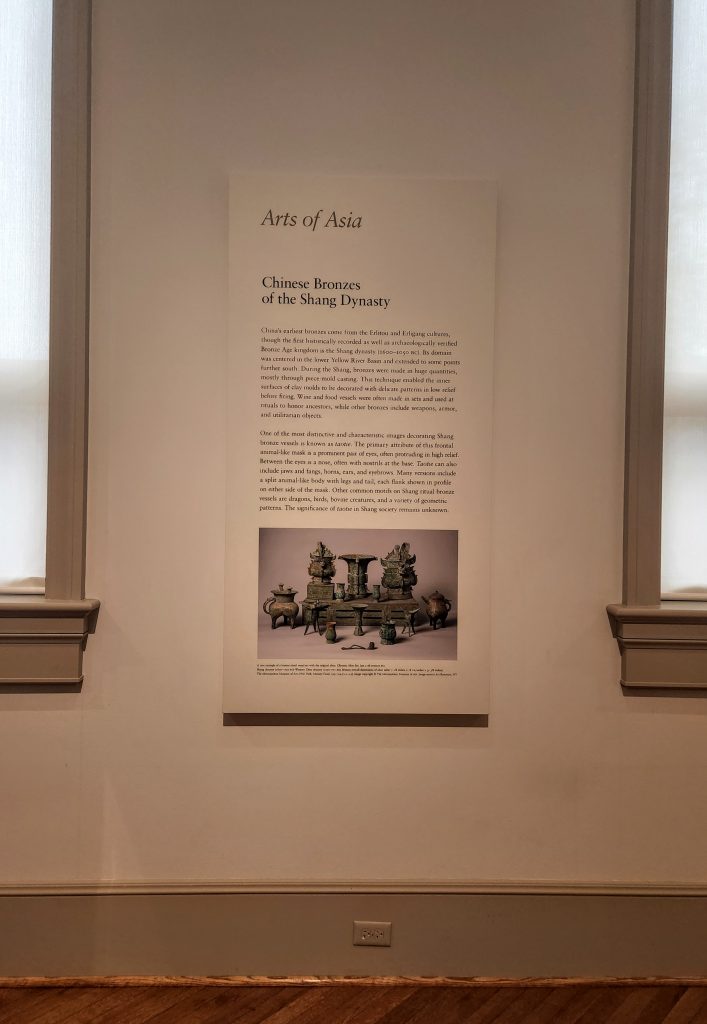

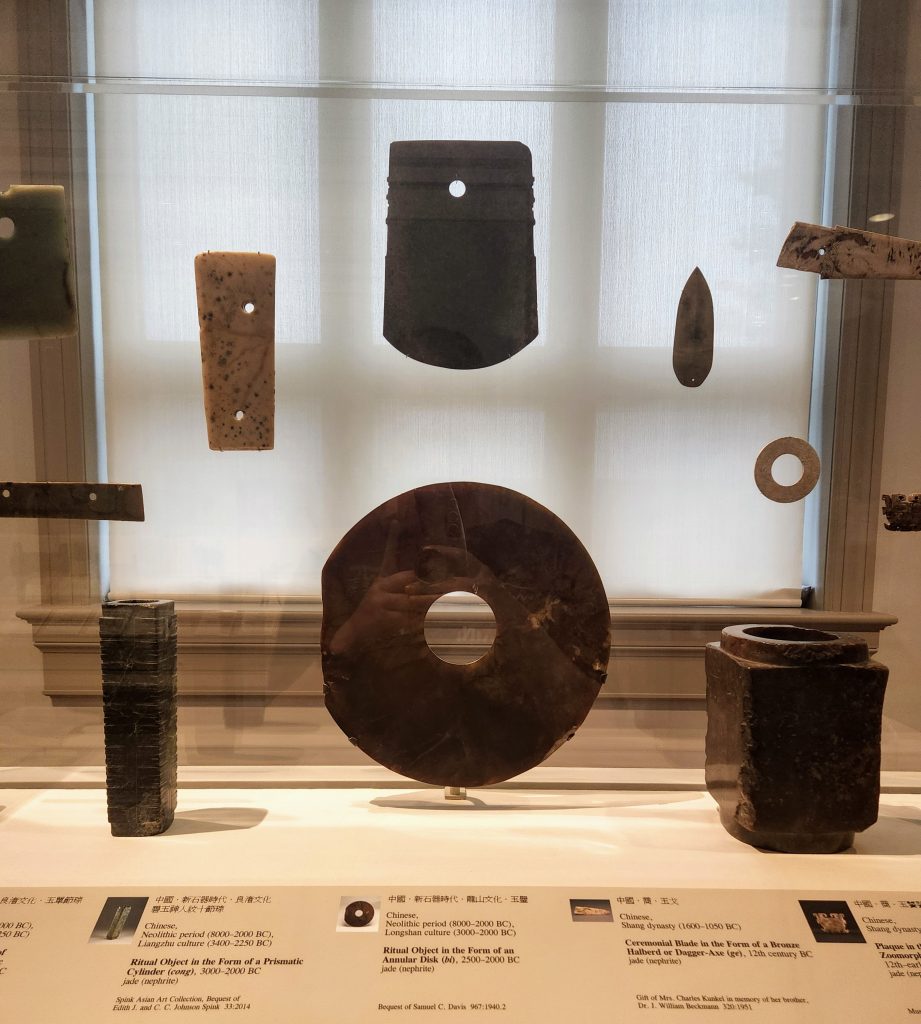

Wall-mounted panels on the left (window) side of the gallery provided context for the exhibit as a whole. Minimally descriptive labels accompanied each object. The combination of interpretive panels and basic descriptive labels worked for this exhibit. With less information accompanying each object, one is given the space to contextualize the artifacts at a slow, contemplative pace, setting the tone for the gallery overall. With so many ritual and religious artifacts on display here, the choice to allow for individual exploration and study (within the chronological framework) makes sense. The first panel at the entrance to the gallery further set the tone: “According to written records and archaeological evidence, jades were used in sacrificial offerings to gods and ancestors, in burial rites, for recording treaties between states, and in formal ceremonies at the courts of kings.”

As visitors move past the first panel and set of cases, we can learn about jade, its uses, and the beliefs tied to it from the earliest days of the region that later became a unified China. Moving chronologically, the exhibit shifts focus from the Neolithic beginnings of Chinese art into the Bronze Age, with case after case of intricately created figures, vessels, weapons, and more. Curators of this exhibit were able to display hundreds of objects within this single, long room by making use of vertical space within the large cases. Mounted via clear rods to the Plexiglass vitrines, small objects are lifted from the pedestal surface to eye-level, allowing for more label room and a more visually engaging space.

The stoic, prayerful atmosphere of the first half of the room was replaced by a feeling of movement and artistic flow as one moves closer to the doorway into the Buddhist gallery. Wine and food vessels allude to the increased opulence in Chinese courts and provide contrast between both the earlier displays of jade and the later collection of Buddhist artworks. It was here in this transitory section that I was struck with the title of this blog post, after looking at the bronze wine vessel below. An interpretive label nearby the object highlighted the unusual elongated neck and three “spouts” at the top. But what was it used for? I read on and suddenly understood the familiarity that this object was giving me – it was a drinking game!

Moving past the collection of Chinese bronze work, visitors finally come to the end of this section of Asian Arts, the Buddhist sculpture gallery. Dominated by a bright polychromed statue, this square room was both a literal and figurative turning point for this exhibit. Having seen so much bronze in both small and large formats, the wood, stone, clay, and gold-plated materials of this room are a clear transition to the adjacent gallery, exhibiting Chinese ceramics. (Because I had surveyed this corner of SLAM when I first entered the gallery, I knew the ceramics rooms were presented differently than the one I had just come from. There, exhibit displays were not organized chronologically but by form and style; while intriguing and undoubtedly important, this gallery would be the end of the line for the purpose of this review.) Instead, I moved to analyze the larger statues in the Buddhist gallery as the culmination of the “progress” narrative of the jade and bronze before.

Ultimately, the first gallery of the Asian Arts exhibit introduced here is a chronological survey of Chinese cultural practices from the Neolithic period through the rise of Buddhism in the region. I believe that the exhibit curators are successful in conveying the idea of forward progression through the objects displayed in this section. The exhibit is highly accessible, as demonstrated by wide walkways, even flooring, bright, well-oriented light, and clear signage. Additionally, all of the object labels in this section had at least some level of bilingual text. Without any knowledge of Chinese writing, I am unable to discern how much of the labels is translated; however, the inclusion of another language at all is a positive step, in my opinion. Additionally, labels here include a color photograph of the object they are describing, which is immensely helpful in areas of high density (a very well-packed case) as well as for descriptive purposes.

The only critique I have for this exhibit is the lack of directional signage…without doing a survey of the area first, it would have been difficult to discern where this exhibit ends and the next begins. Such is the case in a lot of art museums, I feel, as the objects are meant to speak for themselves in relation to those around them. I understand the choice, but for practical purposes, the blurred boundaries between sections could cause a visitor to get turned around, or to not understand the forest for the trees.