West Point in the Making of America, 1802-1918 | Smithsonian Institution (si.edu)

What does the Mexican-American War and World War I have in common? The history of West Point military academy will provide the answer. “West Point in the Making of America, 1802-1918” curated by Barton Hacker and Margaret Vining with the support of staff and several departments of the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution describes the history of the United States’ earliest and most renowned of the five federal academies and the first engineering school in the U.S. West Point’s education of great military leaders has helped secure the United States’ position as a world power.

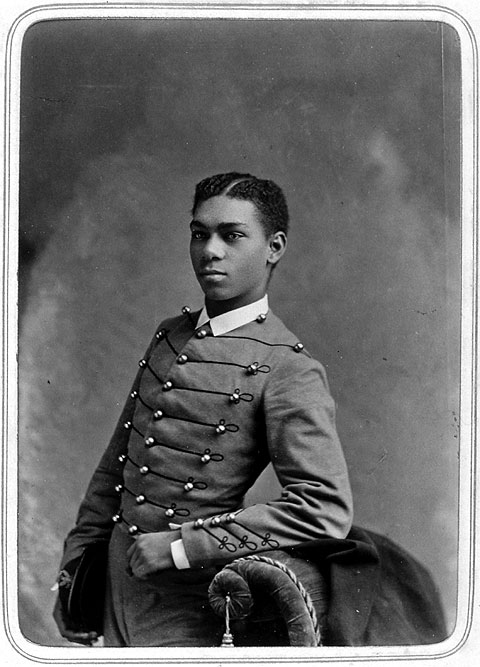

This historically important, highly informative, and well-curated exhibit provides thorough coverage of West Point’s early history concentrating on turbulent times in America’s past from West Point’s founding through World War I. The exhibit provides something of interest for all ages and includes a thorough bibliography for the subject matter. It highlights men of broadly varying backgrounds including one African-American, who graduated and went on to serve in the army in a variety of capacities. Special attention is given to high ranking officers and generals.

Located on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River in West Point, N. Y., West Point and Army USMA is just 50 miles north of New York City. The idea for the military academy was first proposed in 1783 by George Washington but it was initially opposed due to being considered “incompatible with democratic institutions, fearing the creation of a military aristocracy” too much like that of Great Britain. It wasn’t until two decades later, on March 16, 1802, that the United States Military Academy officially opened; Washington having died in 1799 did not see his objective come to fruition. It resides today on its original site. Enrollment at West Point was always highly selective. It was here that many of the most famous (and infamous) and well-respected military commanders began their careers. The honor roll includes Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Robert E. Lee, “Stonewall” Jackson, George A. Custer, John J. Pershing, P. G. T. Beauregard, George B. McClellan, George Crook, Oliver Otis Howard, future president Dwight D. Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur.

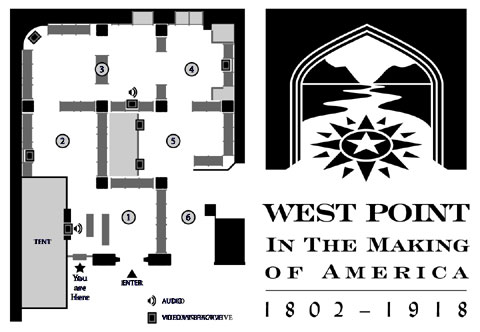

The floor plan of the exhibition at National Museum of American History, Behring Center

(1) Introduction, with a brief history of West Point through WWI

(2) The Antebellum Army, 1802–1860

(3) The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861–1870

(4) An Army for the Nation, 1866–1913

(5) World War I, 1914–1918

(6) Epilogue, on West Point in the 20th century

The design of this virtual exhibit on the early history of West Point provides easy navigation and is organized in a linear/chronological manner though the viewer can dip in and sample sections as they desire. The exhibit is divided into six sections: “Introduction; 1802-1860 The Antebellum Army; 1861-1870 Civil War and Reconstruction; 1866-1914 An Army for the Nation; 1914-1918- America in the Great War; and Epilogue”. Each of these sections highlights their respective time period, the military crises, and the achievements of the graduates including science, education, engineering, and other fields. The exhibit’s epilogue provides a window for examining the Army’s role in the 19th and early 20th centuries; building America’s federal army, exploring unknown territories, and fighting wars to protect citizens and to preserve the Union.

Right: Sword and scabbard used by George B. McClellan during the Civil War.

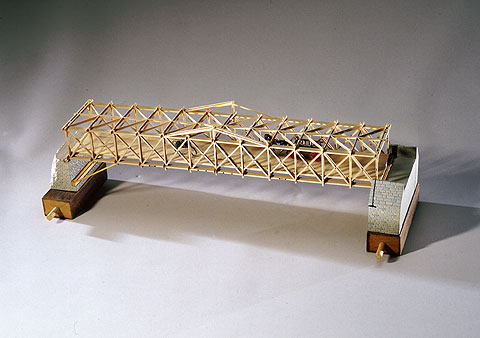

There is more to the exhibit than meets the eye. Visitors can click on most any aspect of the exhibit and reveal a plethora of information including maps of famous battles, paintings and portraits, models of architectural designs, audio and video recordings, photographs, and a broad range of artifacts used by soldiers. The exhibit paints a picture spanning the lives of young cadets to the graduates who would lead the nation and a military academy that greatly shaped American history.

The exhibit’s written content adequately provides an appealing narrative and piques the interest of the observers. In the section tilted “1861-1870: Civil War and Reconstruction”, visitors can access links that discuss weaponry used during the Civil War by both the Union and Confederate armies. For example, the 1863 rifled musket radically increased the range of accuracy and made traditional infantry attacks obsolete.

Users are able to read about the lives of Civil War soldiers who attended West Point. The biographies of West Point graduates incorporates links to personal artifacts and their correspondence. Linked to the brief biography of George A. Custer, visitors will see his role at the last stand at the Battle of Little Big Horn and view personal belongings like the buckskin coat he often wore and his laundry dampener. Artifacts displayed are from the Smithsonian and borrowed from other institutions.

The other five sections of the exhibit continues to highlight major battles and scientific innovations involving West Point graduates, helping visitors understand why the battles were fought: for independence, to restore the Union, or acquire new territory. The exhibit excels in bringing to light the personal history of lesser known soldiers like engineer Robert Parker Parrot otherwise overshadowed by graduates like Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. Clearly West Point’s history has been predominantly based on the lives of educated white men. During the period covered by the exhibit few men of color were enrolled and the first women were not accepted until 1980. Even today though men of color and women have made inroads at West Point the percentage enrolled does not remotely reflect the racial makeup of the United States.

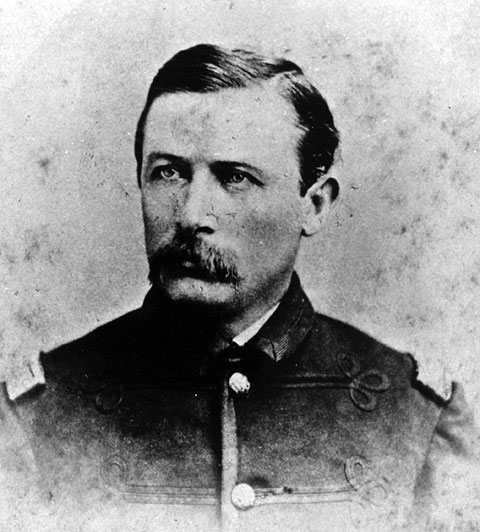

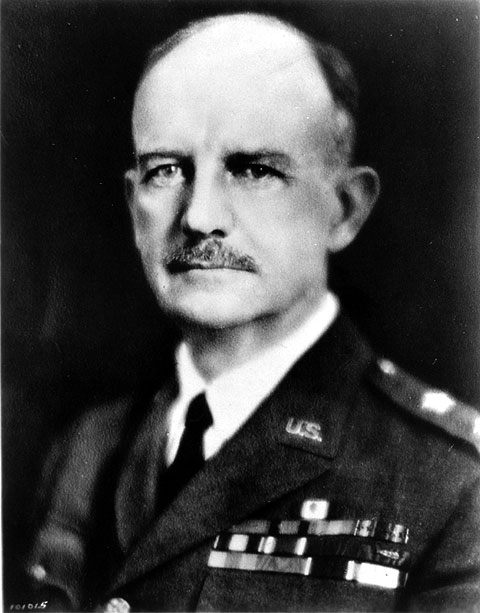

Center: Frank Ross McCoy (1874-1954)-McCoy was assigned to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.

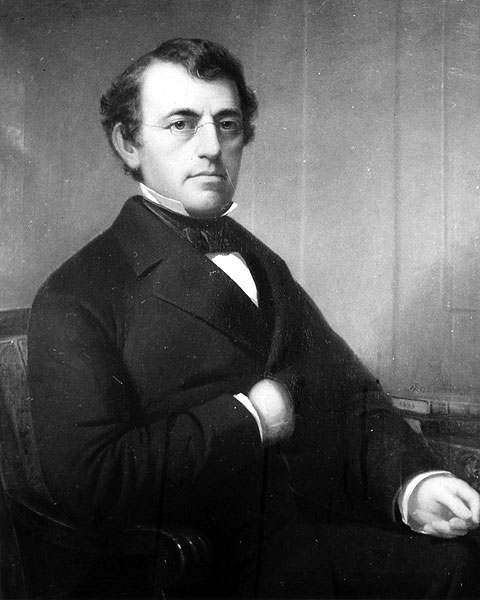

Right: Robert Parker Parrot (1804-1877)-Engineer and academy teacher.

The shortcoming of the exhibit are few. As an online exhibit, legibility of the narrative is important and could have been much enhanced using a larger font in text sections.

The image on the left demonstrates the kind of page layout the exhibit uses as well as how the exhibit is organized. Note that the design of the exhibit uses a mostly dark blue background which obscures some text and the font is small and difficult to read. It would be helpful if entire pages could be magnified or zoomed. West Point in the Making of America (si.edu)

Though the exhibit provides ample examples of artifacts, the captions accompanying them could have been fleshed out with additional information.

The exhibit glorifies the accomplishments of soldiers like Ronald Slidell Mackenzie in battle (section titled “1866-1914: An Army for the Nation”) and the virtues of exploration and expansion/Manifest Destiny on the future economic development of the nation. However, it fails in describing the consequences of these battles on indigenous peoples, their land, and the environment.

West Point’s early military leaders and engineers laid the foundation for America’s military prowess by laying out the history and illustrating the way the United States created an army to defend the country both at home and abroad. West Point’s curriculum shaped a brotherhood of young men; creating military officers who would lead a young nation to victory in the Mexican-American War, Civil War, Spanish-American War, the Indian Wars, westward exploration and expansion, and World War I, but neglected to discuss the consequences of these battles on Native Americans. The general public as well as scholars will find learning about West Point and its role in American history rewarding and eye-opening.

Reed, this is a great post! Military history is not usually my jam, but I really enjoyed reading this. While I was reading it, I had a hard time finding your argument as to why this particular exhibit is important or different from others. (Please let me know if I just skipped over it.) You did a wonderful job of telling us all about what the exhibit consists of, but what about it makes it special?