Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa

The Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time exhibit was organized and curated by Kathleen Bickford Berzock from the Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University. The exhibit was made possible by two major grants provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the Human Endeavor and Northwestern University’s Buffett Institute for Global Studies.

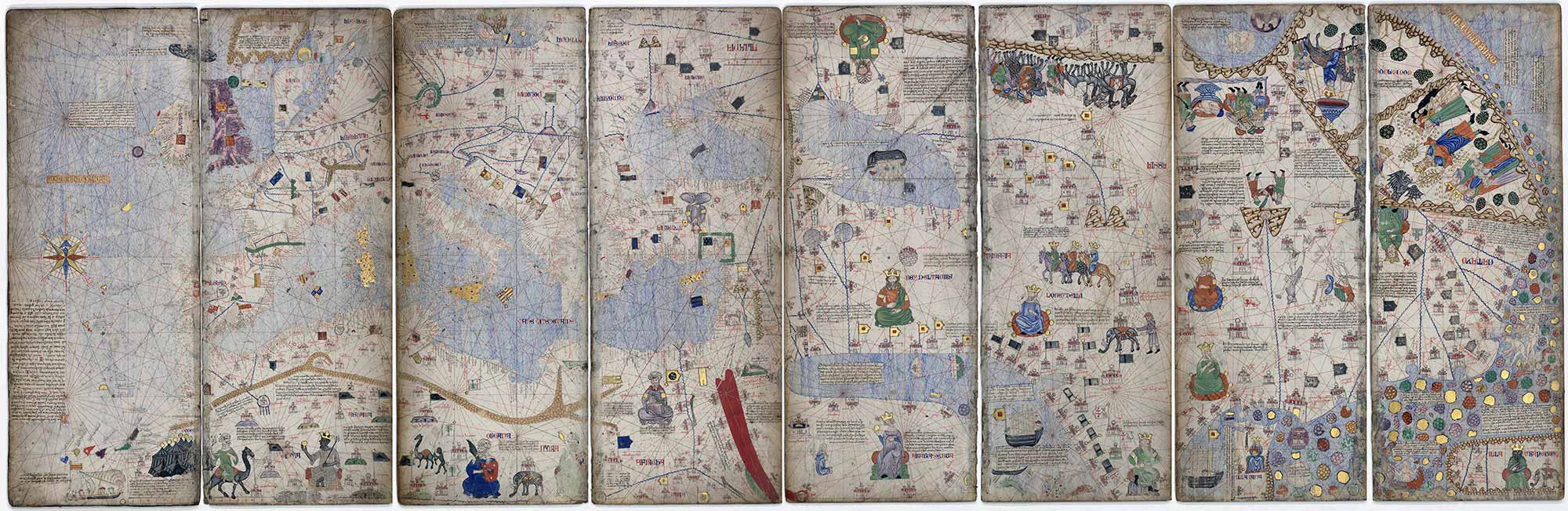

The overall objective of the Caravans of Gold exhibit, is to intentionally place Northern Africa at the center of the world. In regards to trade, international governments, and religion; Northern Africa truly was the appropriate center of the medieval world. It is through video lectures and interviews that the viewer is transported into this Africa-centered model of the medieval world.

The target audience for this exhibit seems to be high-school students and older. While there are not necessarily any complicated terms or names, an elementary understanding of how history has been told makes this exhibit come to life. The heavy use of videos and images, while keeping the text to a minimum, keeps the guest engaged and allows them plenty of places to stop and take in what they’ve heard/seen. One of the unique aspects of this exhibit is the clear bias that permeates the entire project. While bias is most often associated with negativity or unprofessionalism, I believe it is absolutely necessary in this exhibit. By slanting the evidence and the story of the world in a manner that places North Africa at the center, we arrive at a whole new understanding of the medieval world.

It is my argument that this exhibit is vital to the future education of all students of history. Not only does this story re-center the medieval world in a more accurate manner, but it does so in a more approachable way than strict lecturing. The use of video and images supported by text allows the guest to experience more opportunities to soak in the message. The exhibit does not dissect the importance of North African culture, trade, and political power. Rather, it interweaves them based on material evidence which has been discovered and presented.

The above coin above, for example, can be found in one page of the exhibit which discusses the value of African salt and gold in the medieval world. In West Sudan salt was used akin to the currency of the day due to its value. West Africa also claimed some of the purest gold mines in the known world at the time, making it a desirable trade partner for most of Europe. At the bottom of this same section in the exhibit we find a video interview of an African salt merchant who still sells the same goods as his forefathers. This powerful combination of imagery and video really grants the viewer a more stimulating teacher than most traditional museum exhibits.

The exhibit itself is set up with one home page and nine other pages, each with images and videos for the viewer to peruse at their pace. The last two pages are “Teachers Guide” and “Virtual First Look” which again call attention to the exhibit’s desire to educate and enrapture their audience. The Virtual First Look is an actual video walkthrough of the exhibit which allows the viewer to walk through the physical exhibit set up. This reinforces the drive of the exhibit to make the data feel legitimate and approachable to all their viewers.

The exhibit features all kinds of items, from gold coins and pieces of gold-inlayed text, to camel saddles and pottery. All of the images are two dimensional however, and do not allow the viewer a proper size understanding. With each image comes a helpful caption stating what the item is, the date it was created (or a guess), who the creator was (if that’s known), and who/where it was found.

10th to 14th century C.E. – Copper alloy – Direction nationale du patrimoine culturel, Bamako, Mali

I do not think there is anything new about the artifacts themselves, but rather in how they are being presented. While North Africa tends to play a minor role in the medieval world, this exhibit forces the viewer to place it at the center. African gold, rugs, and pottery are removed from our limited definition of “exotic,” and become the norm. This vantage point is what allows the artifacts to speak more clearly to the viewer. They say, “we are not exotic, side-characters in a Eurocentric history. We are our own main characters in an Africa-centric history.” This seemingly radical new vantage points makes the western viewer uncomfortable at being confronted with a world in which Europe is not at the forefront. It is this discomfort and this self-reflection that makes the work that this exhibit does vital to the education of all people. As historians, I believe we can understand and appreciate the work exhibits such as these do in rewriting the history of the world in accordance to material fact, and not through repeating traditional Eurocentric methods.

Despite being virtual, this exhibit does an excellent job in making the viewer feel an attachment and a depth in regards to the objects and the stories around them. Through copious amounts of images and videos, the viewer is more apt to fall in love and feel a deep connection with the goal of the exhibit and those who created it. With this being said, I felt that one weakness of the exhibit was the lack of text. Many images and videos will appeal to people with limited time or shorter attention spans, but deeper knowledge of the materials and concepts could have been displayed through more text. I believe that their amount of text was appropriate, given that their audience is anyone on the internet, yet leaves the academics hungry for more. Perhaps that was the point of limiting the text and allowing the artifacts to speak for themselves!

Reese, I loved your post! This seems like a fantastic exhibit. I really admire your writing style; it is very academic and you get straight to the point, but it is still very approachable. One suggestion that I have would be to break up the text a little bit, either with headings, quotes, or anything else you can think of! The content is more easily digestible when it is broken into thematic sections.