The Context and the Problem

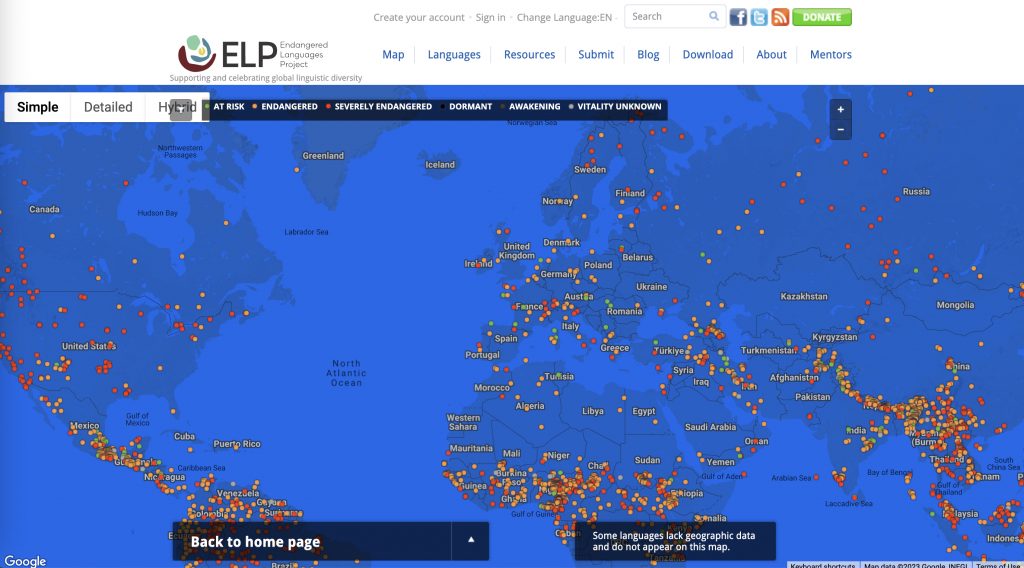

Language endangerment is a threat at a global scale. The Ethnologue identifies over 1,300 languages with the status of shifting, moribund, nearly extinct, or dormant, according to Expanded Graded International Disruption Scale/EGIDS criteria (Lewis and Simons 2010), a grim statistic echoed by other tracking resources. When a language is lost, more than just a code of communication is lost. All languages are tightly tied to the cultures, belief and knowledge systems, the social organizations, and the histories of the communities that speak them, including place-based and geo-spatial, temporal and calendar, flora/fauna, technology, math, and social, economic and political systems dynamics. This makes our knowledge about the world’s languages foundational to shaping our ideas about the human condition and experiences. All world languages, including endangered and under documented languages, are critical to advances in fundamental science and scientific discovery. When languages are lost, and when this linguistic knowledge is lost, there is a similar loss of information about cognitive and social organizations and diversity, cultural histories, and the relationships between humans and the natural world.

Via findings from past and existing National Science Foundation DEL-NEH DEL (now NSF DLI-NEH DEL) projects, we now know much more about the linguistic systems of many vulnerable and endangered languages. Some of this knowledge comes via contemporary documentation methods that yield detailed linguistic descriptions and analyses that have been produced with NSF support (see for example: Sande et al. 2020, on tonal phonology with data from Kru; Harley 2020 on nominalization in Hiaki; DiCanio et al. 2018, with a phonetic description of information structure in Yoloxóchitl Mixtec).

Additionally, the growth of archival infrastructure, also supported with NSF funding, has contributed to this knowledge expansion (for example, the Kani’âina “Voices of the Land” repository, with materials on native Hawaiian speech). And, there are compelling examples of how methods that are beyond the field of linguistics and language documentation can greatly inform linguistic description and analysis (see for example: Gonzales et al. 2018, investigating the traditional knowledge held by Yoloxóchitl Mixtec speakers about stingless bees; McPherson and Ryan 2018, with intersections between tonal phonology and music in Tommo So; Good 2020, with intersections between language documentation in Cameroon and ethnographic, geographic, historical, and archaeological methods; Hu et al. 2018, with methods for multi-media visualization of language and dialect variation in languages of Nepal; DiCarlo 2010, with intersections between language documentation and verbal arts; Chung et al. 2019, connecting Punan hunter-gatherer language research with biomedical and population genetics data).

There are also case studies demonstrating how community collaboration can shape research questions and methods, yielding transformative information about language diversity and linguistic patterns (see for example: Carroll et al. 2018, which adapts media technology to learn more about Native perspectives of themes surrounding ‘land’ and ‘health’; Fitzgerald and Hinson 2016, with community-centered approaches to collecting texts in Chickasaw; Yamada 2010 and Sapién 2017 which illustrate how collaboration with community language experts can lead to more widely-useful outcomes in documentation as well as the discovery of innovative patterns of morphosyntax that might otherwise be overlooked).

A Need to Foster Community

Yet, there is still a need to tap into this demonstrated potential, and to conceive of and build additional projects that cross discipline boundaries in ways that are articulated in the Program solicitation. Our initiative starts with the position that there are project developers and collaborators who will benefit from dialogic interaction that generates concrete examples, and from interaction with people from other discipline backgrounds who either have engaged in convergence-type research activities, or who have held NSF funding in areas with potential overlap with DLI documentation work.

Compounding this need to foster connections across disciplines, academic institutions have traditionally presented knowledge-sharing silos and other barriers. Historically, university departments emphasized specific and delineated areas of specialization, primarily as a way of offering intensive and focused training opportunities for students (Hartwell et al. 2017). However, faculty and students have increasingly recognized the need for skill sets and knowledge that can cross discipline boundaries. Additionally, meaningful and sustained cross-disciplinary collaboration may serve as an agent to break down racial, ethnic, and gender inequalities amongst both faculty and students (Liera and Dowd 2019). There is also growing recognition that cross-disciplinary collaboration is a more effective approach towards solving grand societal challenges that are urgent to our time. These include issues of poverty, social welfare, racial and ethnic inequality, and we would argue, language loss and the accompanying loss of wide ranges of knowledge associated with it.

There is now a greater push for cross-disciplinary collaboration between fields such as STEM and educational research (STEM-DBER), for example (Reinholz and Andrews 2019). Likewise, STEM collaborations with arts and humanities disciplines result in STEAM initiatives, with examples such as “The Arts and STEM” at Miami University of Ohio that fuse industrial design and artistic conceptualizations.

Pivoting to crossovers with linguistics and language documentation, while community collaboration really blossoms once (funded) projects are underway, there are comparatively fewer opportunities for cross-fertilization from different specialists, alongside community input into project conception before the proposal is in and has been reviewed. But there are pushes for this, for example Ruef et al (2019), which documents the involvement of Ichishkíin tribal elders in the designing of indigenous-informed pedagogies to math curricula. Our project aims to use these cases and ongoing challenges as foundations on which to build additional convergence examples and opportunities.

Our Initiative

Our initiative aims to define, exemplify, and promote sustainable, meaningful, and impactful cross-disciplinary language documentation scholarship that more consistently meets the criteria of the Dynamic Language Infrastructure (DLI) program guidelines. The predecessor program of DLI, NSF-NEH Documenting Endangered Languages (DEL), supported research in wide ranges of practice, crossing genres and domains, advancing archival storage and access, and driving deeper and more consequential discipline-specific investigations. DLI now supports projects that use the methods and data generated from language documentation to contribute to data management and archiving, and to aid in the development of the next generation of researchers. The DLI Solicitation describes three areas of emphasis that are ideal candidates for support:

- Language Description: To conduct fieldwork to record in digital audio and video format one or more endangered languages; to carry out the early stages of language documentation including transcription and annotation; to carry out later stages of documentation including the preparation of lexicons, grammars, text samples, and databases; to conduct initial analysis of findings in the light of current linguistic theory.

- Infrastructure: To digitize and otherwise preserve and provide wider access to the documentary materials described above, including previously collected materials and those concerned with languages that have recently lost all fluent speakers and are related to currently endangered languages; to create other infrastructures, including conferences to make the problem of endangered languages more widely understood and more effectively addressed.

- Computational Methods: To further develop standards and databases to make the documentation of a certain language or languages widely available in consistent, archivable, interoperable and web-based formats; to develop computational tools (taggers, parsers, speech recognizers, grammar inducers, etc.) for endangered languages, which present a particular challenge for those using statistical and machine learning, especially deep learning methods, since such languages do not have the large corpora for training and testing the models used to develop those tools; and to develop new approaches to building computational tools for endangered languages, which make use of deeper knowledge of linguistics, including language typology and families, and which require collaboration among theoretical and field linguists and computational linguists, computer scientists and engineers.

Creating, planning, and executing language documentation research that meets any or all of these goals entails that the activities need to make significant and meaningful connections to other disciplines, including those that make use of computational tools and work with large and varied datasets. But making and strengthening these connections requires scholars from different disciplines and for community stakeholders to engage in what the NSF terms “convergence” research, namely, research that involves deep integration across disciplines and that is driven by compelling societal problems. Such research requires that scholars be able to have access to and learn from each other in order to formulate research questions and construct innovative methodologies and collaborative work plans. Such opportunities are not always available across communities, or within a researcher’s university/institution, or in discipline-specific venues.

Establishing a DLI Community of Science

We are members of the initiative “Establishing a DLI Community of Science”. Our initiative addresses these concerns by bringing together linguists who are engaged in impactful cross-disciplinary language documentation work. It also involves key community stakeholders who work both within and beyond the academy, all with planned synergy of ideas and best practices to achieve transformative intellectual merit and broader impacts in areas of computational infrastructure, data management, and convergence research more generally.

The goals and activities of our initiative are in many ways parallel to those advanced by the NSF Convergence Accelerator program, but at a more focused scale. This DLI Community of Science brings together scholars and other stakeholders with diverse expertise, with a goal of developing research questions that address a variety of societal problems made evident by situations of language endangerment and loss. Participants’ varied knowledge and experiences will contribute to a better understanding of questions of process and best practices in cross-disciplinary investigations as well as to developing truly convergent areas of inquiry.

Overlaps between language documentation research and the other disciplines represented by the members of this initiative may reveal transformative questions about the human mind (psychology), social organization (cultural anthropology), population histories, movements, and variation (environmental sciences and archaeology), spatial organization (geospatial sciences), physiological, mental, and community health (social psychology and medical anthropology), and human and natural world connections (biology, environmental sciences, and environmental anthropology). Members of the initiative will also come with their own ideas about ways in which their research might foster further intersections. An overarching goal of the project, and implemented in the planned activities, is to bring people together in an environment that nurtures the sorts of discussions among scholars that lead to innovation in research project design. In this way, our initiative may establish a template based on smaller and more controlled sets of interactions that can be modified and re-used to foster further convergence opportunities elsewhere.