Why Does “Book” Mean Book and Book? – A Research Project by Hope Krisko

Linguists have spent decades attempting to understand all aspects of language and language use. Within their research, they have come up with a category of words called polysemes. According to Sebastian Löbner, “a lexeme is polysemous if it has two or more interrelated meanings”. Polysemy is a result of “a natural economic tendency of languages” that causes language communities to adopt an existing term for a new idea or object that has a related meaning rather than create a whole new term for it (45-46). But what exactly makes a community choose a specific word to adopt? Is there specific criteria? Why do all related concepts not come from the same word? The rest of this page will serve as a case study of two polysemes (arms and book) as I attempt to answer these questions.

Methods

The data in this case study is gathered from a variety of sources. The words were taken from a random list on google and were chosen simply because I found them interesting. The definitions and histories were then taken from the Oxford English Dictionary. Due to the multitudes of definitions available in the Oxford English Dictionary, the first definition available for each individual usage was picked. The only exception is with the first detailed use of “arms” – the first definition given by the OED refers to a different definition for a more modern-day version, which is the definition quoted below. The years in which these versions of words entered into the English language were taken from the “timeline” feature of the OED, which lists the first documentation of words in 50 year increments starting from 1000 and going to just after 2000. Also from the OED are the examples of different forms of the word. For simplicity sake, I excluded the forms that were indicated to be transmission errors and only took forms from Middle and Old English.

The analysis of the history of these words comes in two forms. The first is a set of frequency charts, one for each respective use of the words, that highlights when the different forms of the word quit being used in favour of the term “arms” or “book” respectively. The frequency charts document the usage of these word forms from 1500 to 2019. Due to much of the form variation being in Old and Middle English, only a handful of forms were still in use by the time the 1500s rolled around, so for simplicity sake I only included the forms that showed data on the chart. Additionally, because the chart stems such a long period of time, the use of words is not adequately noted – as can be seen in my analysis of the verb “to book”, word forms that were in use will still result in a flat line along the bottom if they were not popular enough. For clarity sake, any word form that resulted in a flat line along the bottom was discarded from the data as it did not contribute anything to the chart. This data was generated and formatted by a google tool called Google N-Grams. The second form are two timelines, one for “arms” and one for “book”. This timeline shows the history of these words as a whole and when each new meaning got added. These were created with the tool J.S. Timelines.

By the end of the analyses of the word histories, I was left with some hypotheses for why the words “book” and “arms” in particular were chosen. At this point in the study, I turned to other academic works to see if my hypotheses matched any professional theories. These readings were chosen from Southern Illinois University of Edwardville’s Lovejoy Library online database as well as from the Google Scholar database.

Arms

The word “arms” can mean many things – a weapon, a branch of the military, a part of your bodily anatomy. There are a handful of other meanings according to the OED, but for simplicity sake we will just focus on the three mentioned.

Arms (noun) – “weapons of war or combat; (items of) military equipment, both offensive and defensive; munitions”

According to the OED, this version of the word “arms” is a borrowing from the French language sometime between 1200 and 1250. The borrowed word is “armes”, which translates to “weapons” in English. The word was borrowed during the Middle English era of our language and saw many different forms including armez, armis, armys, harmes, armes, before eventually becoming “arms”.

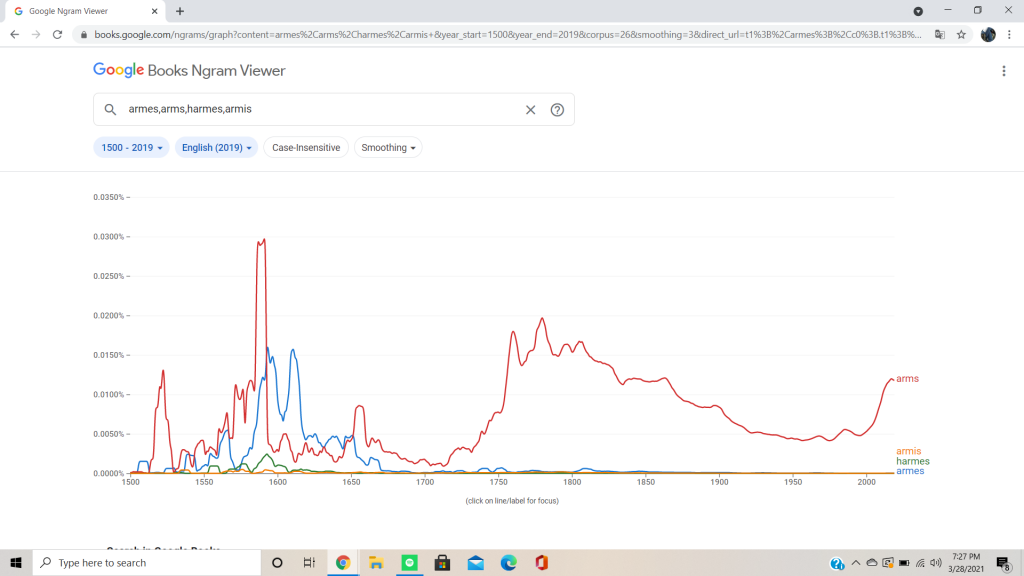

Below is a frequency chart that shows the contrast between four forms of the word: arms, armes, armis, and harmes. The red line, which signifies arms, shows that it has been the most popular form since the 1500s (with the exception of a brief period between 1600 and 1650 when “armes” was the popular form). Harmes and armis in particular were never as popular as the two previous forms, and they both fell out of use before 1650. “Armes” became rarely used post-1650 with a just a couple small spikes in popularity until 1850, when it fell out of use completely and “arms” became the sole English form.

Arms (noun) – “the upper limb of the human body, or the part of the upper limb between the shoulder and the wrist”

This version of “arms” was a word inherited from English’s Germanic roots and was first seen in English between 1000 and 1050. This version of the word , clearly much older than the previous, can be traced all the way back to Old English. This version of the word also has many more forms than the previous, including eorm, hearm, erm, earm, eærm, ærm, and arm from Old English and æarm, earrem, herm, arrm, arum, arme, and harm from Middle English.

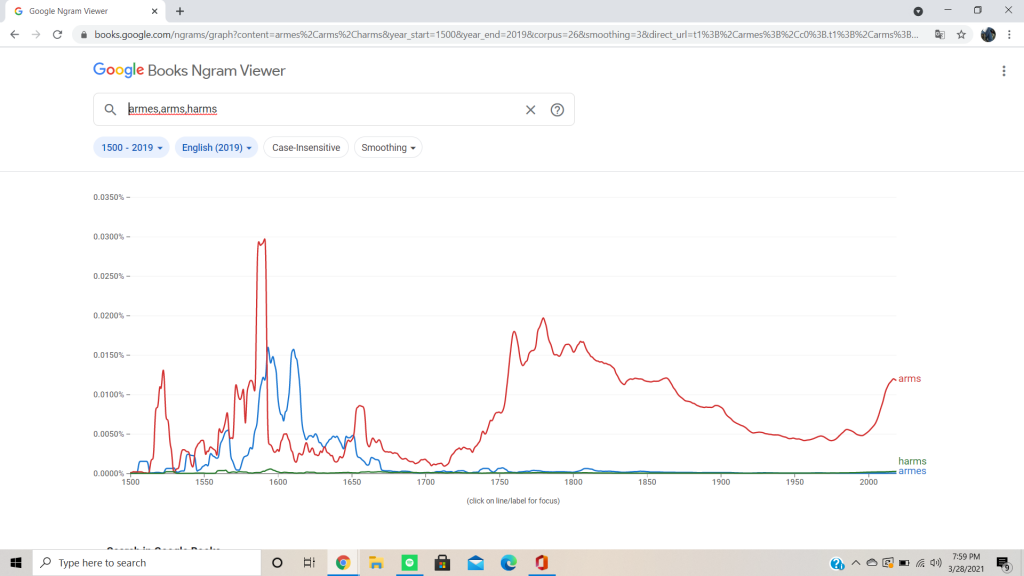

The frequency chart below charts the forms “arms”, “armes”, and “harms”. It is important to note that it looks very similar to the previous chart due to the repeated trajectory of “arms” and “armes”. The chart does not discern the exact meaning of the word, so the popularity could be for either use. I will not repeat the same analysis for “armes” and “arms” as before, but note that both versions were much more popular by the 1500s than any other version. The only other version used with any sort of regularity was “harms”, and that was only between 1550 and 1600. At the end of the scale, “harms” seems to be gaining in popularity, but I must remind you that “harms” is not just a form of “arms”. In modern English, it is a word all on its own, meaning the act of harming another. I would safely assume that the popularity spike of this form at the end of chart is due to this modern-day meaning.

Arms (noun) – any major divisions of the army, as the infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineers, etc.; a distinct or specialized division or branch of any of the armed forces

According to the OED, the origin is “probably a variant or alteration of another lexical item”. It was introduced into the English language between 1750 and 1799.

There is not a frequency chart for this form of the word because there are no alternative forms given in the OED.

Comparsion

It is clear that definitions one and three of “arms” are a perfect case of the definition of polysemy. While there is no direct evidence of where the third definition comes from, I would say that is likely derived from the first definition as the meanings are very interrelated (both have to deal with the military). This makes these two words an exemplary case of polysemy, where a language recycles a word with a similar meaning instead of coming up with a new word entirely for a concept.

In contrast, consider the second definition of “arms”. This version of the word has a completely different history and no relation to the other two versions of the word in meaning. This sort of relation is called homonymy, a phenomenon where “two lexemes share all distinctive properties (grammatical category and grammatical properties, the set of grammatical forms, sound form, and spelling) yet have unrelated meanings” (Löbner 44). Interestingly enough, you can see where definition one and two of arms came to share the same word orthographically (and perhaps phonetically). Refer to their historical forms. Definition two comes to match definition one (which was adopted from the French word) around the time of Middle English so that both versions come to use the forms “arme”, which eventually gave way to the “arms” we have today.

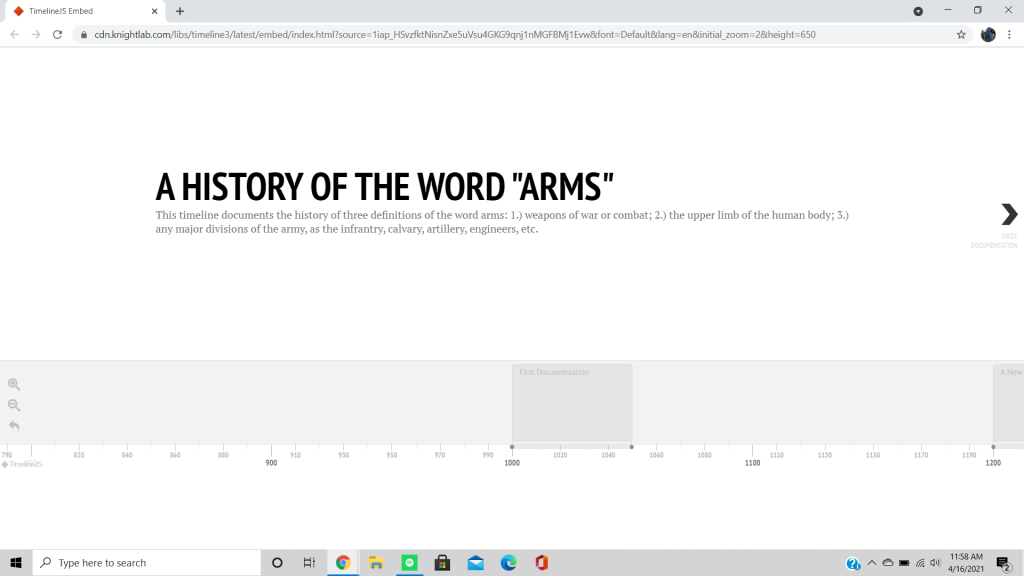

Here is a short timeline to show the evolution of the word “arms”:

Book

Like “arms”, the word “book” has multiple meanings. Book can mean both something that you read and an act of official documentation.

Book (noun) – “a portable volume consisting of written, printed, or illustrated pages bound together for ease of reading”

This use of “book” comes from Germanic roots. It was first documented in Old English (it entered the English language between 1000 and 1049)and has had many different forms historically including baec, beoc, boec, bæc, bec, becc, bocc, booc, boc, bech, bocan, bok from Old English and beec, beoken, boche, boec, boch, bocke, bogke, bok, bowk, bowke, buckys, buke, bock, boke, buk, booke, book, bowkes, boykes, bucke, boocke, bouke, boouckes, boock, and beuk from Middle English. For a time reference, the form “bock” (in Middle English) marks the start of the 16th century uses.

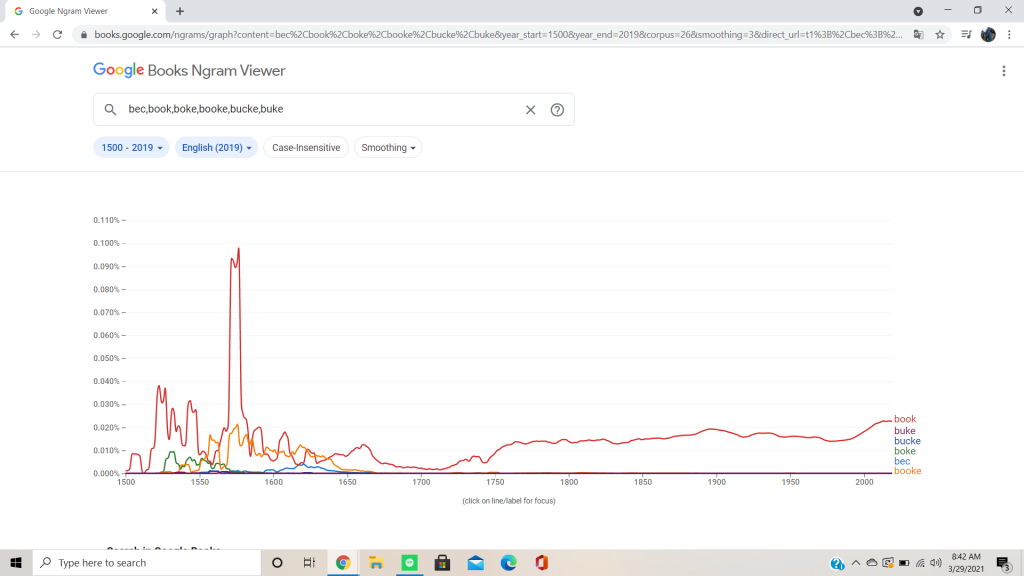

Below is another frequency chart showing the popularity of these different forms post-1500. Of the forms with data, “buke” and “bucke” were both rarely used. The form “buke” had minimal popularity in the mid-1500s. “Bucke” was slightly more popular than “buke”, but only for a very short span shortly after 1550. “Book”, naturally, is the most common form and has been since 1500. The form “booke” is the second popular form, although only from the early 1500s to late 1600s (with a brief popularity spike again around 1750). “Boke” was popular for a brief period of time in the mid-1500s and “bec” was used from roughly 1550-1650, with most of it’s popularity being within the second half of that time period.

Book (verb) – “to record in a book and related senses”

Like the noun, this use of “book” comes from Germanic roots and was originally used in Old English with the form “bocian”. This version of the word was also introduced into English between 1000 and 1049. “Bocian” is the only Old English form, with the remainder coming to fruition in Middle English. These forms include bocað, gebocad, ibocket, boke, booke, and book (which began to be used in the 1500s).

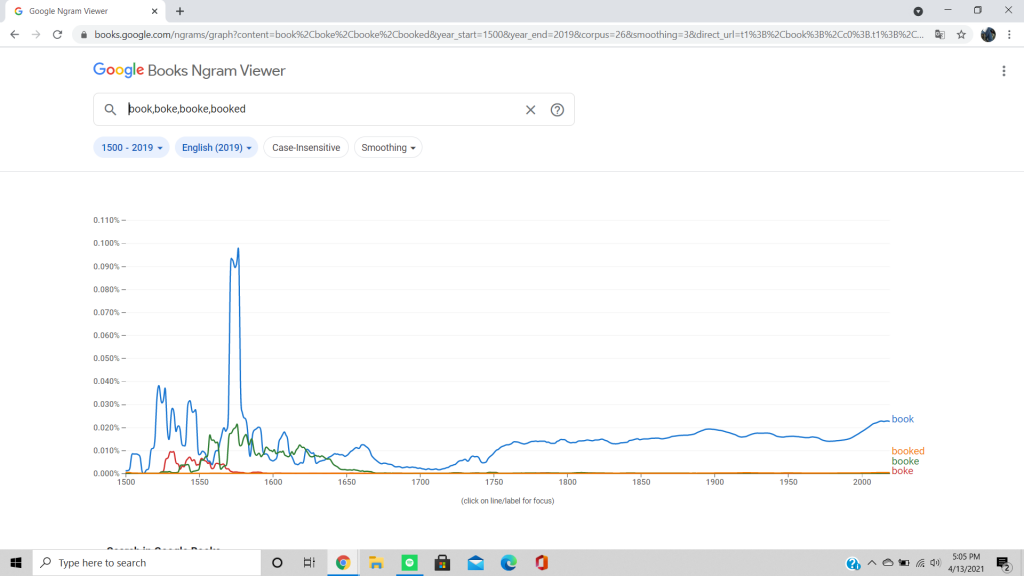

The frequency chart below mirrors the chart from the noun version of “book”, however it differs in two ways. For starters, with this chart the only forms used were “book”, “booke”, and “boke”. My analyses of these three forms are in the section above the other frequency chart, but this chart allows for a more in-depth view of how their popularity changed. Take a look at “book” for example, which was at a few points (just after 1550 and again on and off from roughly 1600 to 1650) only the second most preferred form and for one very brief point between roughly 1525 and 1550 the least preferred. Secondly, different tenses were included to see if it would help pin-point when the verb itself began to be used rather than the noun form. The present tense, “booking”, resulted in a flat line along the bottom so it was discarded, however the past tense, “booked”, does show a slight increase in popularity since the early 2000s. Before then however, the data resulted in a flat line so it is hard to tell when the verb form really began to be used.

Comparsion

It is easy to see how these two words are related (the verb “to book” involves recording something traditionally within a book of some form). Additionally, both forms of the words have the same origin – they stem from Germanic history and were introduced during the time of Old English. While they may have had different forms at one point, as our language evolved and certain forms fell out of fashion, it seems that it was decided to give the popular form of one version to the other version as well, giving a case of polysemy. Note that the use of the term as a noun is much more popular than the verb form.

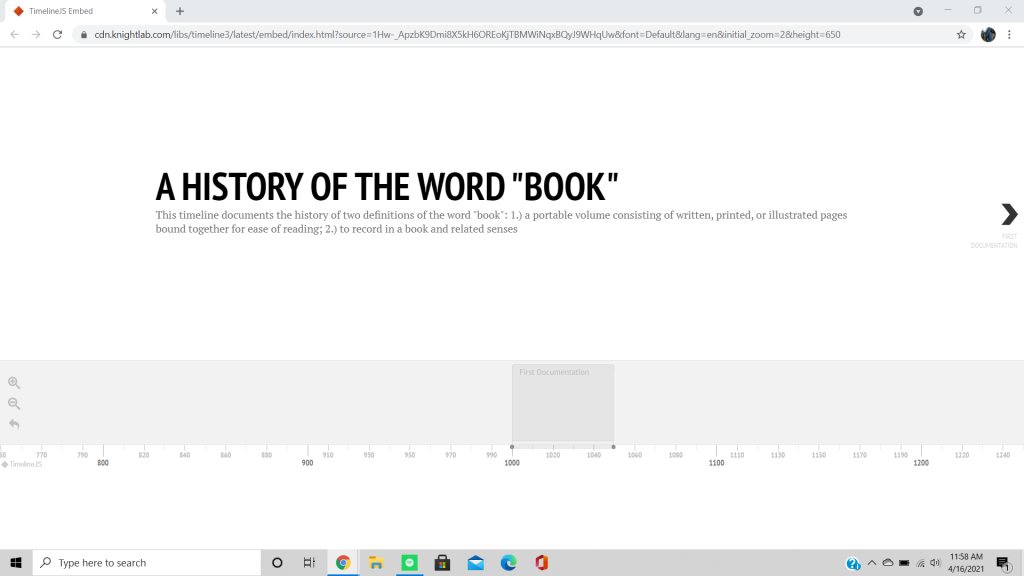

Here is a short time-line that recaps the changes this word has undergone:

Analysis

From this brief study of the two words, multiple aspects of word-meaning relationships and polysemy are available.

For starters, we have learned that word relations are often complex. Look at the three different versions of arms – two of the definitions have a polysemous relationship while the third has a homonymous relationship in reference to the other two. This specific case highlights that while two versions of a word may have one sort of relationship, it does not mean that all versions of the word have that same relationship. The relationship that meaning variants of a word have is not something that can be generalized – it is subjective.

Secondly, we learn that polysemes do not necessarily have to evolve out of the creation of a new concept. Look at the word “book” – while the two meanings did not originally share a word, the evolution of language caused one to adopt the form of the other.

Thirdly, we have seen that just because a word can have multiple related meanings does not mean that all of those meanings are equally as popular (the verb form of “book” is much less popular than the noun form).

But that still leaves the question: why was the term “book” chosen as the form of the word that survived language evolution? And why was the word “arms” chosen to mean a branch of the military and military weapons? From what we have seen so far, I hypothesize that in some case such as “arms”, it was chosen out of convince. As for cases like book, I hypothesize that the forms of these two distinct meanings evolved to look more and more similar until they just became one (potentially in pronunciation first, and then in orthography). To help answer these questions, I turn to literature.

Literature Review

According to Ingrid Falkum in her piece titled “The How and Why of Polysemy: A Pragmatic Account”, there are two differing ideas on how polysemy is created. One idea is based on the rules of linguistics which says polysemy happens with a certain amount of linguistic knowledge in hand, and the other idea is based off of pragmatics, which says polysemy happens with new interpretations of a word aside form what the default linguistic meaning intends. Falkum mentions the downsides of looking at polysemy from exclusively one lens or the other but ultimately concludes that the pragmatic idea is most likely the way polysemy arrives as it accounts for non-verbal cases of polysemy as well as verbal ones. Due to this idea, she describes polysemy as a “fundamentally communicative phenomenon” that “arises as a natural consequence of lexical meanings not being able to fully encode speaker-intended senses” (35).

Another article by Falkum, this time in partnership with Augstine Vicente, titled “Polysemy: Current Perspectives and Approaches” adds onto the ideas found in Falkum’s other essay. In their paper, they talk about regular (or logical) polysemy versus irregular (or ambiguous) polysemy. They state that for regular polysemy, a “literalist” or rule-based approach is the best explanation. These explanations included the “dot object” postulation, which involves complex representations and an underspecification approach, as well as coercion, which takes a literal meaning of a word, mashes it with other literal word meanings in the sentence, and produces a new meaning (21). They also propose lexical pragmatic processes, which enable communicators to give new meanings to existing words, as an explanation for polysemy (24) and cognitive grammar approaches, which say word meanings are conceptual categories and all the different possible meanings (senses) are sub-categories to the general sense (26).

Hugh Rabagliati’s work, “Rules, Radical Pragmatics and Restrictions on Regular Polysemy”, talks about how regular polysemy is created (which is through rule-based linguistic principles). This idea of “regular polysemy” is mentioned in Falkum and Vincente’s article and deals with shifting between two conceptual ideas in a given semantic field with lexical rules such as producer-product (so it slightly different from the form of polysemy we are talking about in this study) (3). Interestingly, their study concludes that children are more likely to develop polysemy pragmatically however. Their study also found that while children can follow the rules of polysemy, they can also overestimate the upper boundary of it and are picky about which senses are acceptable (32). While Rabagliati’s study may not apply directly to the form of polysemy in this study (which involves meanings rather than shifts in semantic fields), it can still shed some light onto how the human mind handles the idea of polysemy and is therefore worthy of consideration.

In Rochelle Lieber’s book, Morphology and Lexical Semantics, which talks about the semantics of verb formation in particular, she discusses the difference between “sense extensions” (the conceptual, pragmatic approach) and “logical polysemy”, which arises from the composition of word skeletons and their underdetermined meanings in particular (11). With her analysis, she concludes that polysemy with the affixes she was studying (-ize and -ify) “follows from a single skeleton which is interpreted in a number of ways depending on the bases with which it combines” (89). Her conclusion gives support to the more lexical, semantic creation of polysemy. Note that like with Rabagliati’s work, Lieber’s book does not deal with polysemy in exactly the same context as this study, but it is still worthy of consideration because of the light it sheds on how the human mind handles the idea of polysemy overall.

In contrast to the lexical support of the previous article, Robyn Cartson’s piece “Polysemy: Pragmatics and Sense Conventions” argues that “[s]ome of the senses of a polysemous word are pragmatic (inferred in context), some are semantic (conventionalised, mentally stored, directly retrieved) and most of these latter are pragmatic in their origin” (117). Cartson’s argument clearly takes a primarily pragmatically based stance, and she extends that focus into new lexical innovation (meaning the creation of not just new senses or new meanings, but new words based off of existing words as well) (109). She also states that there is a “very general ‘meaning’ constraint” on the creation of polysemous words, meaning the different meanings are “interrelated but are not restricted to a common template” (127). Note that she takes a slightly less constrained idea than other linguists who propose a “core meaning” for all other meanings to be derived from.

Zabotkina and Boyarskaya’s piece, “On the Challenge of Polysemy in Contemporary Cognitive Research: What Is Conscious and What Is Unconscious”, views polysemy from a cognitive semantics stance. In this article, they discuss how polysemy is both a cognitive phenomena in the instances where new meaning is formed via social interaction and an unconscious phenomena as it is an inherent aspect of language use (so it is not realized until a tangible connection between the phonological word and concept is made) (28). They state that “[m]eanings are flexible and adaptive in nature” and “… word meaning is nothing other than a generalization, that is, a concept” (30). The study also states that the meaning of a polysemous word is determined via cognitive context (37). In sum, this article seems to support the idea of a conceptual linking between word meanings (the pragmatic approach). Interestingly, this study also supports the idea from Rabagliati’s essay that children are picky about polysemy and often reject using multiple uses of a word (36).

Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems that as far as polysemy is concerned, the words chosen to become polysemous are chosen either due to lexical reasoning or conceptual similarity to the new meaning attached to them. Why each word is picked seems to depend on the word at hand and what form of polysemy is being created, however the general consensus is that these words are chosen pragmatically (via conceptual similarity) more so than semantically (via lexical reasoning).

It seems that my hypothesis for “arms” (that it was chosen out of logical convenience) is likely to be true. As far as my hypothesis for “book” goes (that the words happened to evolve to look like each other), there is the possibility for that to be true, however it is also likely that conceptual linking also played a part in the creation of this polyseme. For example, the Old-English verb form “bocian” potentially could have been created in relation to the Old-English noun form “boc” (because verbs usually stem from existing nouns), which would mean a conceptual link was made before both forms evolved to be the same word lexically.

A final thought: a third question I proposed at the beginning of this study (why are all related concepts not polysemes) has remained unanswered due to having little relevance over the course of my study. So why are there closely related words, such as stream and creek, that remain their own words and not polysemes? Does it stem from the size of a given language (for example, English is a large language with many specific words compared to many other languages such as French)? Or was there a point in time where it was necessary to differentiate between the two concepts so that they have remained their own concepts? Could they eventually come to be two meanings of same word? These are questions requiring future consideration.

Works Cited

“Ambiguity.” Understanding Semantics, by Sebastian Löbner, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2013, pp. 44–46.

“arm, n.1.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/10808.

“arm, n.3.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/36319175.

“arms, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/10809.

“book, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/21412.

“book, v.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/21413.

Carston, Robyn. “Polysemy: Pragmatics and Sense Conventions.” Mind & Language, vol. 36, no. 1, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2021, pp. 108–33, doi:10.1111/mila.12329. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/mila.12329

Falkum, Ingrid Lossius. “The How and Why of Polysemy: A Pragmatic Account.” Lingua, vol. 157, no. Apr, Elsevier B.V, 2015, pp. 83–99, doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2014.11.004. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/58928/Falkum-Lingua-2015-postprint.pdf?sequence=2

Falkum, Ingrid Lossius, and Agustin Vicente. “Polysemy: Current Perspectives and Approaches.” Lingua, vol. 157, Elsevier B.V, 2015, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2015.02.002. https://philpapers.org/archive/FALPCP.pdf

Lieber, Rochelle. Morphology and Lexical Semantics. Vol. 104. Cambridge University Press, 2004. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MnCcvEUbLToC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=why+are+polysemous+words+formed&ots=XU-dNIL3Oz&sig=74D40dFQS5t1YKCu9n5Z0l7C2b4#v=onepage&q=why%20are%20polysemous%20words%20formed&f=true

Rabagliati, Hugh, et al. “Rules, Radical Pragmatics and Restrictions on Regular Polysemy.” Journal of Semantics (Nijmegen), vol. 28, no. 4, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 485–512, doi:10.1093/jos/ffr005. https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/files/8596562/Rules_radical_pragamatics.pdf

Zabotkina, Vera I., and Elena L. Boyarskaya. “On the Challenge of Polysemy in Contemporary Cognitive Research: What Is Conscious and What Is Unconscious.” Psychology in Russia : State of the Art, vol. 10, no. 3, Russian Psychological Society, 2017, pp. 28–39, doi:10.11621/pir.2017.0302. http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2017_3/psych_3_2017_3.pdf