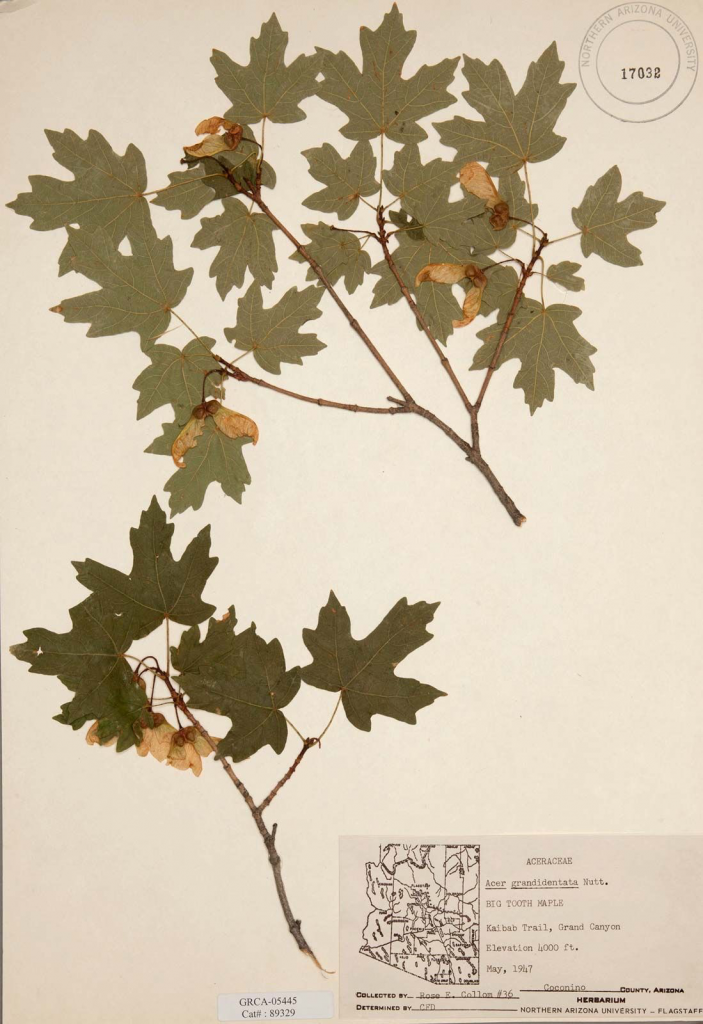

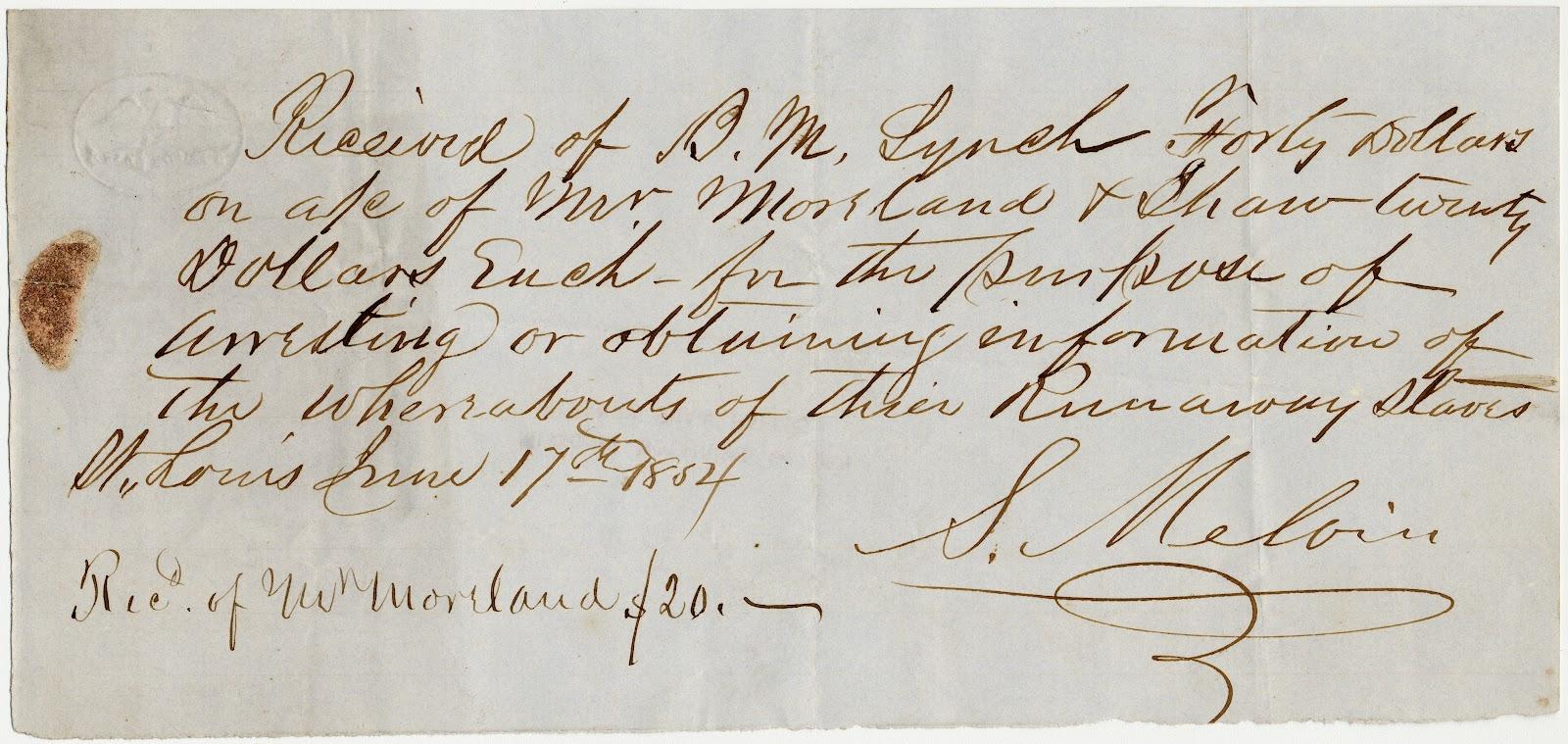

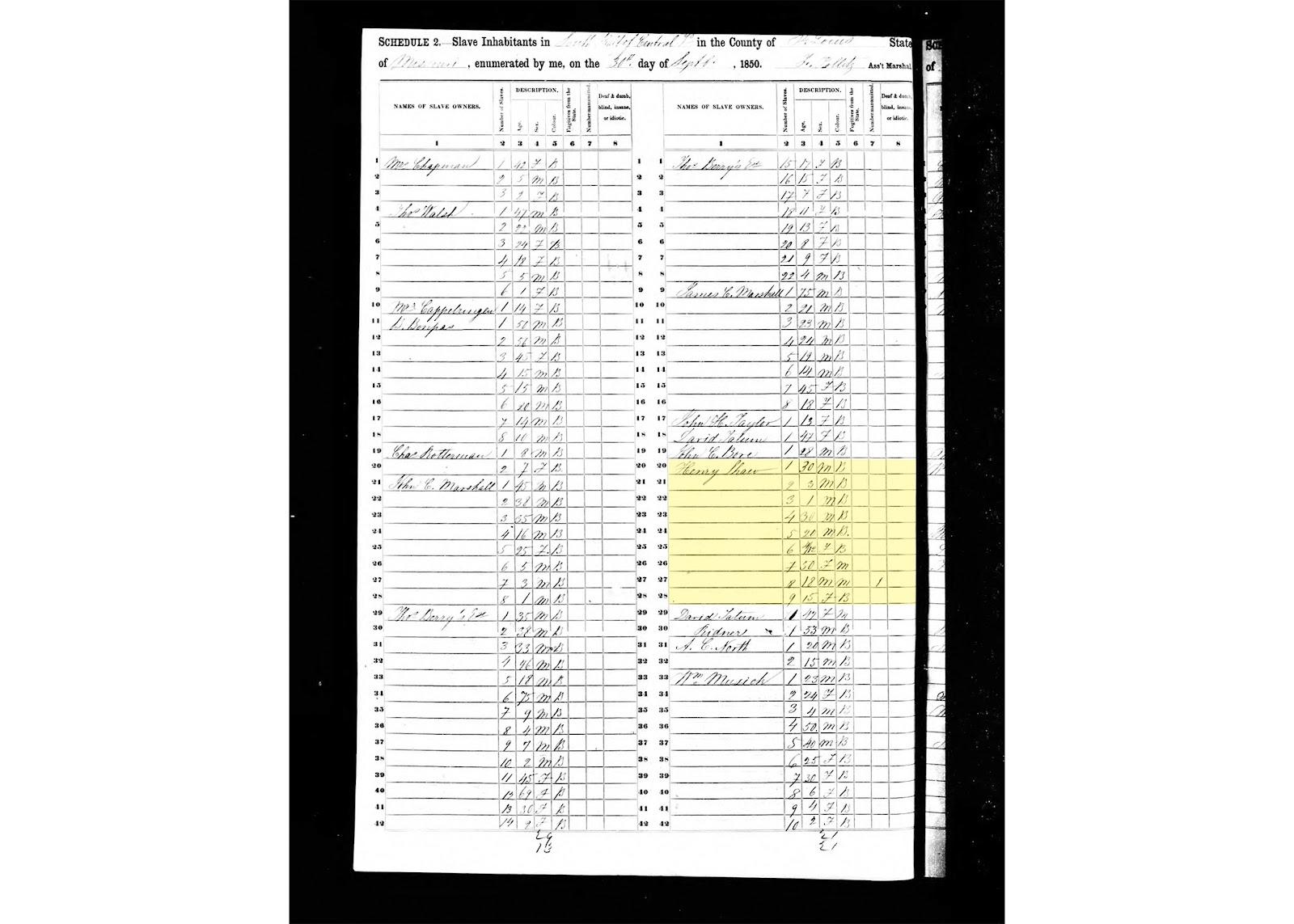

In our findings within the CODES research teams, my team dove into the history of African American knowledge within the garden. We discovered that the contributions of enslaved people to botany often go unrecognized or unacknowledged. These enslaved individuals lacked proper credit for their botanical discoveries. We aim to rectify this injustice by centering their stories and prioritizing reparative justice throughout our research. This semester we used surveys as a tool to hear directly from MOBOT. Our questions included some of the following: “How well do you think the gardens currently represent African American culture, history, and contributions?” and “What strategies or approaches do you suggest for effectively integrating African American knowledge into the garden’s initiatives?”.

In analyzing the findings from both the survey and my time conducting research with my team, several themes and patterns emerged that shed light on the significance of Black representation and engagement within the gardens. Many participants believe the garden does a slightly good job at representing African American Knowledge, some say not well at all.

One significant theme that emerged was the desire for more diverse programming and representation within the Gardens. Many desire to see more events, exhibitions, and educational programs that highlight Black culture, history, and contributions to the field. One response from the survey states we can do the following: “Signs all around the garden. Celebrating and highlighting African American holidays, history, community, events, and employees. Opening access to the garden for efficiency.” This theme is particularly significant as these challenges of botanical gardens are solely dedicated to the study of plants and biodiversity, highlighting the need for these spaces to also serve as platforms for cultural exchange and celebration.

Something I found interesting while conducting the in-person interviews with the MOBOT employees was the significance donors have to the garden. Most, if not all donors at MOBOT are older, white, and upper class, and because they have a voice in where their money goes, African American Knowledge is not a top priority for most unfortunately. What can be done about this? Diverse programming and representation within the Gardens would be great. There is a huge lack of diversity within the staff and I believe donors can help with this problem. Donors can establish endowments to provide scholarships and fellowships for African American students and researchers interested in studying botany and related fields. By providing financial support for education and training opportunities, donors can help cultivate the next generation of African American botanists and scientists, ensuring their knowledge and perspectives are represented and valued within the botanical community. Many participants in the survey were white, this continues the need for diversity within the garden.

Moving forward, our research indicates the need for the Missouri Botanical Garden to confront and address the historical injustices perpetuated against enslaved individuals. This might involve initiatives such as creating educational programs and exhibits that highlight the contributions of enslaved botanists, establishing partnerships with descendant communities, and implementing policies that prioritize reparative justice. By centering the stories of these individuals, the Garden can work towards creating a more inclusive and equitable environment for all visitors.