Priscilla Kincanon

Hildebrandt

CODE 120

20 Sept. 2023

MC #1

A societal or cultural problem is referred to as a “wicked problem” when it cannot be resolved because of a lack of information or knowledge that is inconclusive, a large number of people and points of view, a heavy financial burden, or the interconnectedness of the problem with other problems. Wicked problems are characterized as problems that cannot be solved; on the contrary, easy fixes are problems that have a straightforward and fast way of solving them. An easy fix seeks to solve the immediate problem but may not solve the underlying problem.

The Missouri Botanical Gardens can be seen as a wicked problem. Page 68 of our class text, Sustainable World, talks about the six characteristics of wicked problems. These characteristics are vague problem definition, undefined solution, no endpoint, irreversible, unique, and urgent. The Missouri Botanical Gardens fits under a wicked problem because it goes with these characteristics.

The first characteristic is the vague problem definition. There is diversity among stakeholders. Not everyone will agree with the issues that go along with the problem. There are many factors like geographic locations, different capacities to deal with it, different cultures, beliefs, values, and informal norms. Slavery played a crucial role in both the history of the United States and the city of St. Louis. Slavery left a lasting impression on our state, our city, and the Missouri Botanical Garden, from the Missouri Compromise to the legal dispute between Dred and Harriet Scott to the deeds of notable people in St. Louis history, such as Henry Shaw.

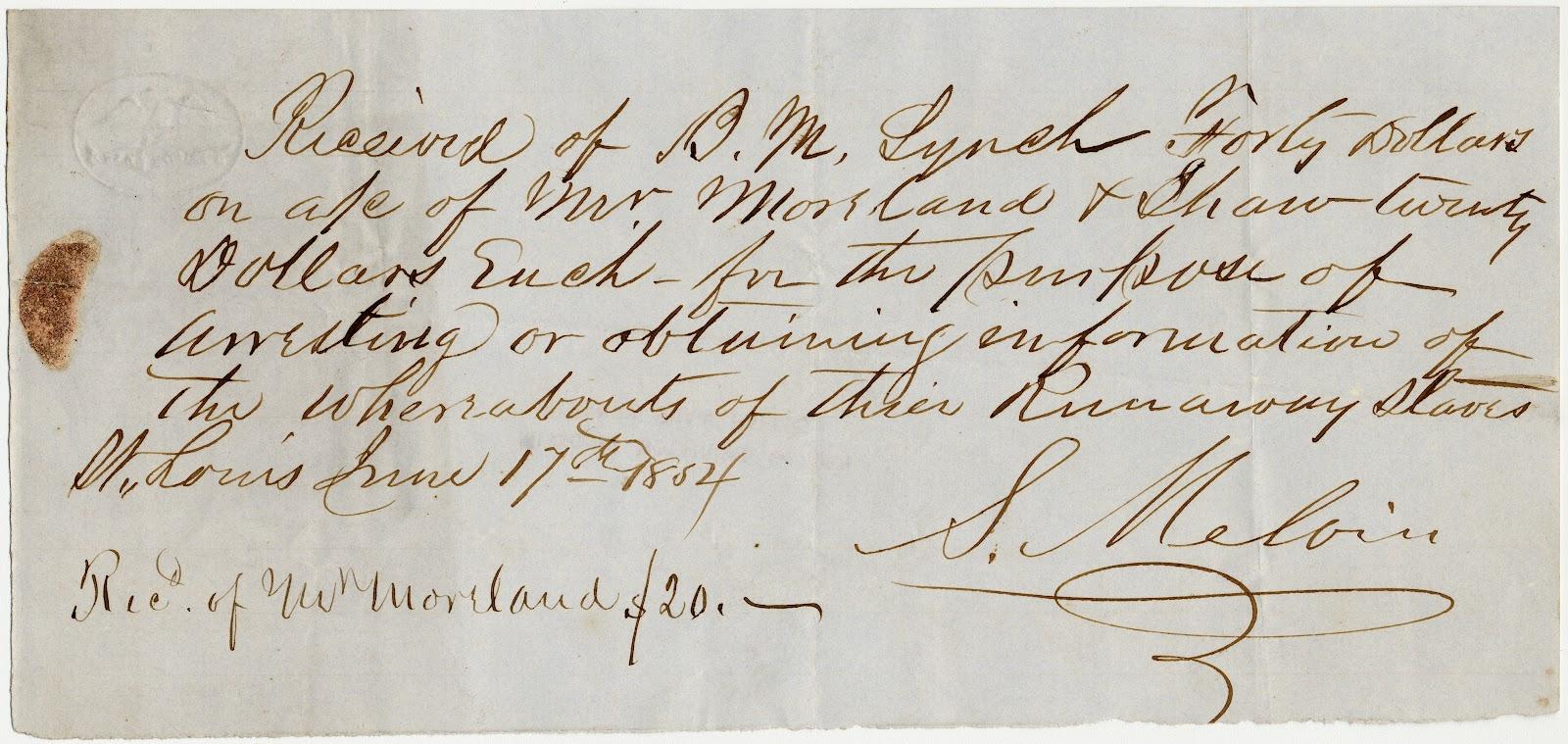

The next characteristic is the undefined solution. There is no definite solution when there’s a wicked problem. MBOT has a few methods. Most of what we know about the people enslaved by Shaw comes from archival records—bills of sale, tax records, census records, newspaper ads, and an early version of Shaw’s will. Examination of these records and the broader history they represent was carried out in collaboration with organizations and institutions that engage with challenging history.

Another characteristic is that there’s no endpoint. There are no final solutions to wicked problems. This is one of the methods MOBOT is using. More than 30 pages of pertinent documents from The Garden’s archives have been converted to digital format. We wish to provide others the chance to conduct their own study about the lives of the people featured here by making these source papers freely available to the public.

The fourth characteristic is irreversible. The text says “Implementing a solution creates changes in the world that cannot be undone and will have real consequences.” (Remington-Doucett, 68). The garden is working on good solutions. Here is another one. The Garden continues to provide interpretive programming, displays, signage, and significant methods to communicate this heritage with our neighborhood. They invite everyone to continue on this path toward being a welcoming community.

The 5th characteristic is unique. There are certain factors that go into a wicked problem that mean that the same solution will not work in all places. There are factors like cultural, political, social, environmental, technological, economic, and other issues depending on the problem. Shaw’s contacts with slavery were not isolated, which in no way excuses his behavior. Henry Shaw’s history is entwined with the histories of St. Louis, Missouri, and the United States as a whole. In this way, the recording of Shaw’s personal history aids in our comprehension of this larger history.

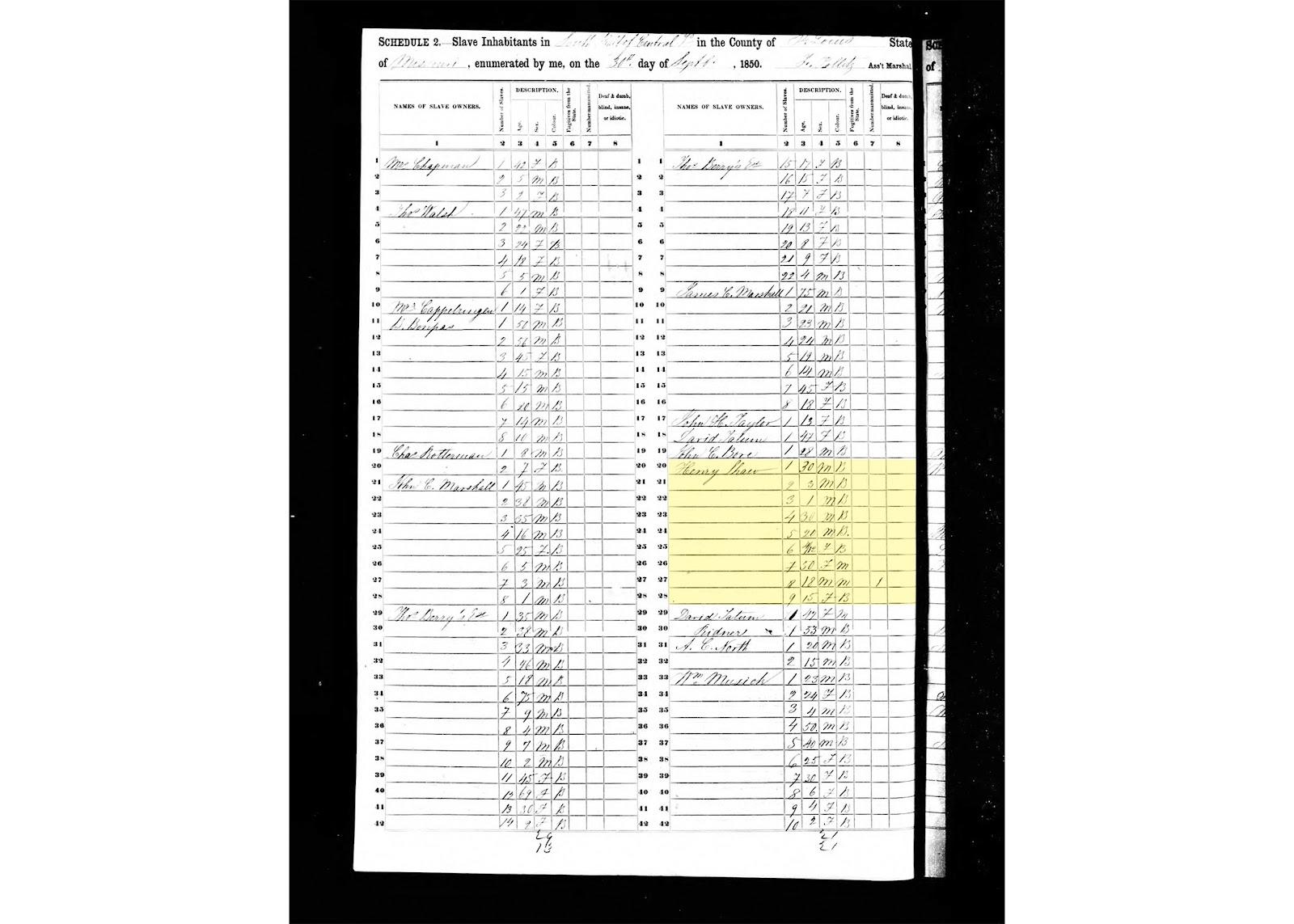

Characteristic number six is the one of a wicked problem and it is urgent. If there is no action right away, it could result in permanent harm to humans and/or natural systems. The textbook, Sustainable World, states “solutions must often be pursued prior to fully understanding the problem.” (Remington-Doucett, 69). The garden is working on fully understating the issue. The Missouri Botanical Garden webpage is where I get this next information. While keeping his city townhouse, Shaw opened the Missouri Botanical Garden in 1859 and spent a lot of time at Tower Grove House. Again, the lack of documents makes it difficult to determine where or for what types of jobs these slaves were employed.

Based on the material at our disposal, we are unable to declare with certainty if the Garden itself was constructed by slaves. It seems likely that Shaw’s slaves at this time were doing forced domestic labor at Tower Grove House, such as cooking and cleaning, based on the ages and genders indicated in the 1860 census.

The Garden is dedicated to expanding on its efforts to share the narratives of Shaw’s slaves and to draw attention to other individuals and underrepresented groups who have contributed to the Garden’s current success. The garden’s behavior and its duty to the community it serves are informed by understanding and respecting this past. To make these stories a more prominent part of the visiting experience, the Garden is actively reviewing the signage and display space on this wicked problem.

Leave a Reply