Tower Grove Neighborhood, St. Louis, MO: Reparative Justice

The 2027 class of CODE Scholar will work with the Missouri Botanical Garden with an inclusive theme of reparative justice, an approach centering on those who have been harmed, focusing on healing and repairing past harms to prevent them in the future. The combined scholarly expertise of ethnobotany and conservation biology, with the historical resources of Henry Shaw’s papers and the specimens in the herbarium, make MOBOT an ideal site for transdisciplinary problem-solving.

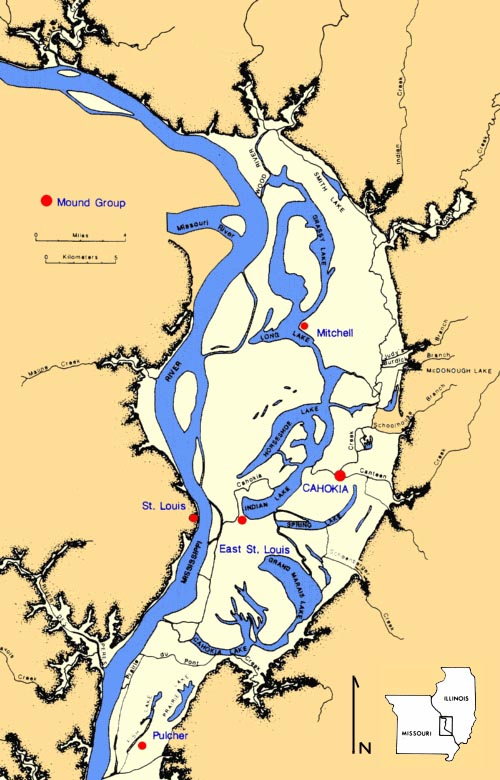

CODE Scholars will work over a period of two years in research teams with Michelle Bonner, Robbie Hart, and Andrew Colligan to explore the institution’s history of enslavement, retrace the erasures of Black and Brown residents who lived in the area that is now Shaw Nature Reserve, and study the indigenous knowledge and cultural context underlying specimens in the Herbarium.

CODE Scholars can help MOBOT tell these stories with intentionality and sensitivity to welcome more diverse guests to the Garden.